Johan Carlsson started part-time hacking in May 2021 and is already number 7 on our HackerOne Top 10 list. How did he get there in such a short time, while juggling a full-time web development job, as well as being a husband and father? Read on to learn about his unique approach, which is a great roadmap for anyone wanting to start – or improve – their hacking game.

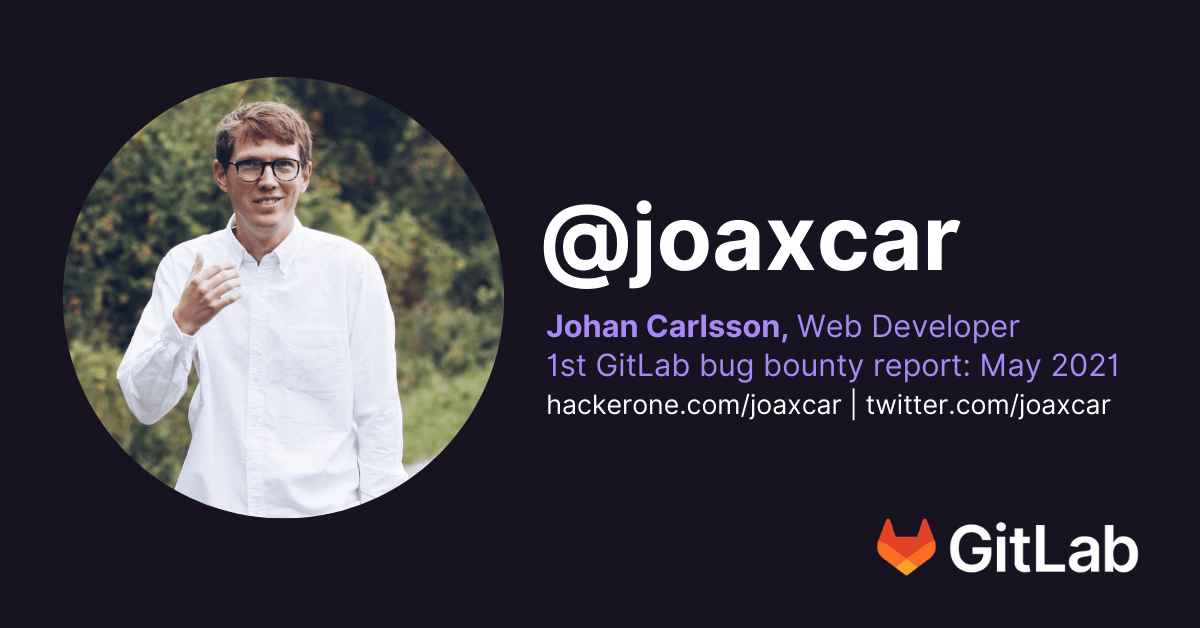

But first, a bit about Johan Carlsson (@joaxcar):

Johan lives in Gothenburg, Sweden, with his wife and their three kids. He has bachelor’s degrees in computer science and fine arts. In his after hours, when the kids are asleep, he looks for bugs in GitLab from the comfort of his sofa. He stumbled into IT security and bug bounties through a course in ethical hacking during his last semester at university.

A year ago, he didn’t know what XSS, CSRF, RCE or any of that fancy jargon was, and he considers himself far from a professional hacker. He says he is learning as he goes. When not at the computer, he spends time with his family, or, more accurately, when he is not spending time with his family, he tries to do some bug hunting.

Check out the replay from our live Ask Me Anything session with Johan:

It starts with the mindset

Q: It’s pretty impressive that you were able to go from “zero knowledge” in bug hunting to landing in our top ten. What aspects of your approach help you to be successful? Any tips for other newcomers when it comes to diving into bug hunting?

Johan: I think persistence and a genuine interest in the subject (in this case IT/web security) is key here. If I were only doing it for the bounties, I don't think I would have been able to continue searching during the days/weeks when I was not able to find any vulnerabilities. For me, I have found as much joy and excitement in learning and researching as in actually finding bugs.

One thing that I have found particularly useful is being able to set my mind to the state of an attacker of the system. It might sound trivial, but when you come from a background of building things, it can be challenging to understand how a feature you built could be abused. When I now look at a new feature in GitLab, this is always my first question, "Ok, how could this break, what could go wrong?"

What makes a great bug bounty program?

Q: I see you’ve diversified and about half your HackerOne reputation points come from other bug bounty programs! Have you seen anything cool in other programs that we could consider implementing?

Johan: Yes, I have been trying my luck in some other programs as well! Mostly it has been to be able to try out other parts of bug hunting that are not very applicable to my work on GitLab, such as automated tooling and more basic "off the shelf" bugs from the OWASP Top 10.

The one thing I have encountered that I somewhat miss in GitLab's bounty program is a more personalized triage experience. A great thing with GitLab's approach to triage and payouts is that it is very standardized and predictable (both triage communication and payout amount). But this is also the biggest downside for me as a returning reporter, and someone who doesn’t consider bug hunting a job; a more engaged and personalized approach would give someone like me as much encouragement to continue in the program as high bounties would.

I really enjoy the programs that run promotions, that have an active program page and encourage reporters by rewarding bonuses when reports are especially well written, interesting or novel. It is a balancing act I guess, as these activities could risk tilting the program and making it "unfair." These types of incentives are also maybe easier to implement in private programs. But still, even the November bug challenge gave me an extra boost as it diversified the incentive to engage with the program.

🆕 Additional insight from Johan:

I really wanted to win the keyboard swag in the November challenge. I was stressed that I had not had time to hunt during November but found some time during the last week. I really tried to focus on finding something fun and managed to send in this report – “Arbitrary POST request as victim user from HTML injection in Jupyter notebooks” – with a finding that I am really proud of. It didn't land me the keyboard, but it did end up giving me my highest bounty I’d earned to that date. 😃

📝 A note from GitLab team

We really appreciate this feedback and understand that changes we’ve made to make our program (and triage process) more efficient and scalable have caused some disappointment across our hacker community. Our intent truly is to make the experience of finding bugs on our platform one that embodies the GitLab values of collaboration, results, efficiency, diversity, inclusion and belonging, and transparency, and we’ll continue striving to balance our need for efficiency and results with our desire to make this a collaborative, transparent and inclusive program. We value the feedback we receive and are constantly looking at ways to improve our program, including response times, collaboration and fun things like contests and incentives. 👀

👉 On that note, we're super excited to share the news of a new CTF we've just launched. Capture the flag and a $20K USD bonus is yours! You can get all the details via our Bug Bounty program on HackerOne. 🎉

How to identify targets

Q: How do you pick which part of GitLab you’re going to dig into? Do you read our release posts? Do you look at old bugs?

Johan: My approach here is very haphazard. It is a mix of reading release notes and looking at old bugs and random issues on the GitLab issue tracker. I use all three of these to identify areas of the application that I have missed or never thought of.

Reading through the release blog posts (especially the monthly security release) has probably been the most fruitful for me. I have reported multiple bugs that are alterations or bypasses to previously fixed and disclosed reports. I usually read through the report, try to understand what caused the problem, and then use my own understanding of GitLab to identify if any edge cases exist where the developers might have missed adding protection. Here’s an example in HackerOne where I did just that!

A bit more random, but fun and rewarding, is to just jump in to issues on the tracker that seem to discuss something interesting. I have found quite a few features that I didn't know existed by reading discussions in issues where GitLab staff and users discuss something completely unrelated to security. I then go to the documentation and the source code and try to identify where this feature resides and start poking at it. Here’s an example of a report I made after doing some digging through public issues.

🔎 More details from Johan:

For example, this External Status Checks documentation page introduced the feature and also contains links to issues and epics under "version history." This is usually a good entry point, and I’ll then try to find some merged merge requests related to the feature and look at what files are modified. I want to get an understanding of where the feature resides in the codebase.

However, I sometimes have the reverse issue, when I find a code path that looks dangerous but I don't know how to reach it from the UI or API. One such instance led me to a series of bugs found in an area of GitLab that I’d never poked at before. (These bugs are just recently fixed/getting fixed, so disclosures have not yet been made.)

The best part of this combined approach to "reconnaissance" is that I can do it on my phone. This is a great feature of the GitLab bug bounty program, as the time I actually have available in front of a computer doing bug hunting is quite restricted.

🧐 real-life example from Johan:

I remember finding this issue, “Improper access control for users with expired password, giving the user full access through API and Git” on my phone while lying in the dark on the floor after tucking my kids to sleep last summer :). It was a reintroduction of an issue that I had already reported. I found a discussion where users experienced some problems connected to the fix (without knowing it) and the issue got introduced again. I realized that the issue existed just from reading the MR. And I just had to get up and test my hypothesis.

Want to know more? Watch the replay!

Learn more about Johan’s workflow, which information resources he relies on to stay on top of his hacking game, and what tips he’d offer up to those looking to start bug bounty hunting in the YouTube live playback and check out the notes from our call with Johan. For a deeper dive, see all of our Ask a Hacker AMAs here.

Keep up with Johan Carlsson by following him on Twitter and checking out his hacktivity on HackerOne.

If you have a question you’d like to Ask a Hacker add it to the comments and we’ll include it in an upcoming AMA!

About the GitLab Bug Bounty program: The overarching goal of our bug bounty program is to make our products and services more secure. The program is managed by our Application Security team. Since launching our public bug bounty program in December 2018, we’ve received over 3,618 submissions, resolved 1025 reports, awarded more than a million dollars in bounties and thanked 478 hackers for those findings. You can see our program dashboard at https://hackerone.com/gitlab.