One of the earliest forms of intelligence was to simply answer the question “How many?”. Counting is one of the first things that we learn as a child. As we grow older, we come to see this deceptively simple concept as somewhat childish. Yet, upon the concept of counting, the entire discipline of statistics is founded. In turn, every discipline that benefits from statistics owes a debt of gratitude to the very humble concept of counting.

Many of the massive data lakes we keep are essentially vast amounts of counting. Using artificial intelligence to analyze this data, we frequently find insights we were not expecting. So it would seem that counting is somewhat of a fractal concept – it’s deceptively simple, but, when compounded, generates delightful things.

So if we have a thing we are trying to be more intelligent about, our first endeavor might be to count it. Let’s see how to apply that to our code stored in GitLab.

Why developers count code

The following list is from real-world scenarios. Many of them are also asserted in Ben Boyter’s blog post Why count lines of code?. Their enumeration here is not an endorsement of the validity or accuracy of code counting for the claimed benefit and the fundamental assumptions of such models are not stated. Because code counting is essentially a form of modeling, it is also subject to George Box’s axiom: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

- Showing the languages in a repository using an absolute metric like source lines of code helps to quickly assess if one can contribute to the project, given their own talents.

- Cost assessment for anything which charges by “lines of code” (some code scanning and development tools may charge this way).

- Although research shows that lines of code are not a good metric for measuring contribution, some developers have gotten used to seeing lines of code per contributor.

- Code base shrinkage as a measure of good architecture (simplification).

- Anything where the complexity of code affects project agility and costs. For instance, assessing and reporting status on migrating a code base to a new language.

- Staffing a development team – understanding what language competencies are needed across the team and in what relative proportion to each other or understanding that for the entire organization’s codebase.

- IT tooling decisions to support the needs of an organization given the most used coding languages across all repositories in the org.

- Assessment of tech debt.

While it is easy to create bad models with any of the above counts, the focus of this post is to get some good counts from which you can carefully build a model.

Toolsmithing GitLab CI: A working example as a shared CI library

The easiest way to differentiate between a “toolized” and “templated” solution is that you can simply and easily reuse this exact code without needing to change it. Many formal coding languages have the concept of shared libraries or dependencies that are essentially toolized. A templated solution consists of a starting point that you customize and then have to manage the code yourself. These can function as scaffolding for a starting point for an entire project or snippets of code that do a specific function. The fundamental difference is that when you use a template, you end up owning and managing the resultant code going forward.

In GitLab CI, we can create our own tooling or dependencies with a few tricks stolen from Auto DevOps. These tricks are:

- Use includes to reference the shared managed library code (this creates a “dependency” on code that is being managed outside of your own).

- The includable code must be written like a function where all needed inputs are either passed in, or can be collected from the environment. No hard coding is allowed because that means you’ve created a template which can’t be depended upon directly.

- Use GitLab CI ‘functions’. I am coining this term to indicate that in GitLab you can precede a job name with a “.” (dot) and it will not be executed when it is read. Then you can create a new job using all the code in the “dot named” job and add variables by using the

extends:command keyword. By using dot named jobs in your includable code, the developer consuming the “managed shared CI dependency” can decide when, where, and how to call the toolized code.

The result: A code-counting GitLab CI extension

Here are some of the final design attributes of this code counting solution:

- Is extremely fast for the given task.

- Leverages the Git clone opitimizations lessons contained in this article: How much code do I have? A DevSecOps story.

- Uses the lightning fast, open source code counting tool SCC by Ben Boyter.

- Is implemented as a reusable GitLab CI shared library extension.

- Allows configuration of the file extensions that should not be checked out because they do not include source code to be counted.

- Leverages the GitLab Run Pipeline forms capability.

- Can enumerate and count an entire group hierarchy in GitLab, or be given a stipulated list.

- Uses the runner token to access and read repositories by default, but can be given a specific token.

- Uploads HTML and text artifacts that contain the code counting report.

- Purposely emits the code counting results into CI logs for easy reference.

The output

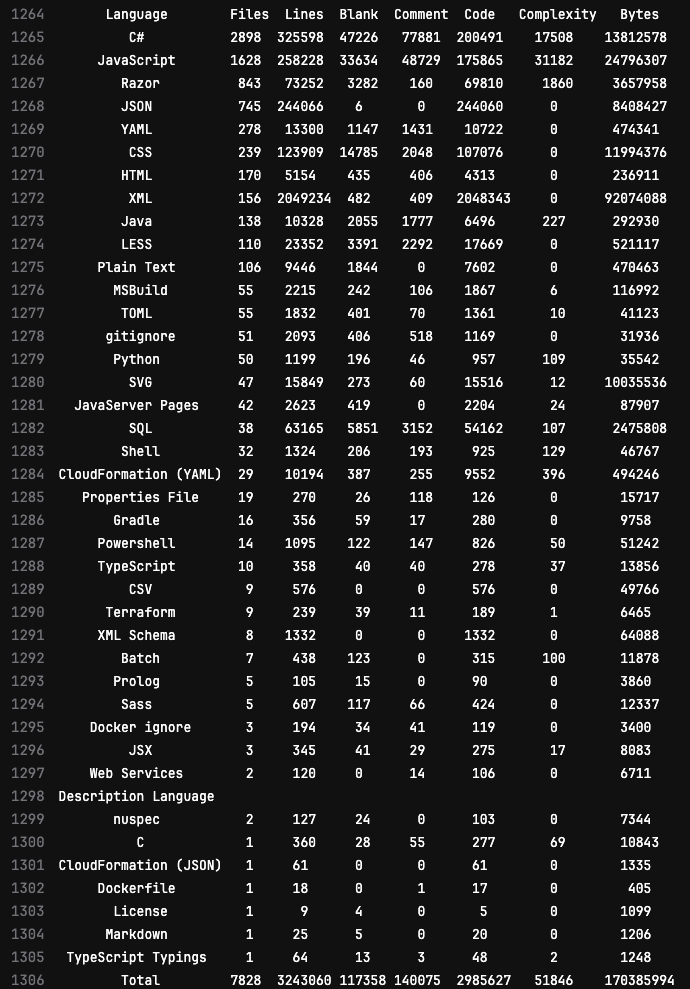

Results are shown below in the CI log but they are also captured as an HTML artifact.

The clone time is also in the log for each project so that it can be verified that the cloning optimizations are making a substantial difference.

These particular results are counting all the code in https://gitlab.com/guided-explorations.

The code

The code is available in this project: https://gitlab.com/guided-explorations/code-metrics/ci-cd-extension-scc. You can view the scanning results in the job logs of past runs here: https://gitlab.com/guided-explorations/code-metrics/ci-cd-extension-scc/-/pipelines.

Rather than fail the entire job when a project fails to clone, the job simply logs the error from an attempted clone. This allows review of valid use cases for not being able to clone and obtains as complete of a picture as possible. The cloning error log is uploaded as a job artifact and emitted to the log.

Innovation: MR complexity metrics extension

During a customer engagement I was asked whether there was a way to assess how much change a Merge Request contained and mark it. This was because an operations team was missing their SLAs for deployments due to the amount of change, and, therefore, risk and review could be highly variable. However, since there was no way to estimate this without human eyes on it, MRs with a high degree of change would overrun their SLA when they couldn’t be pre-triaged.

I wondered if I could use the previously built code counting solution to count diffs and get a rough idea of how much change had occurred in the commits of an MR branch and then apply labels to MRs to give at rough idea of their degree of change as a sort of proxy for how much review time might be required.

It turned out to be plausible and you can review the Shared Library in Git Diff Revision Activity Metrics CI EXTENSION and see the results in the MRs list of this working example project that uses that code: MR list for Diff Revision Activity Analytics DEMO.

The value of remote work water cooler conversations

I have to let you know why this blog was written now when this solution has been around for quite a while. You often hear about how working remotely does not allow for water cooler conversations, which in the story you’re told are where real innovation happens.

Within GitLab’s Remote First culture it is expected that anyone in the company can schedule a “coffee chat” with anyone else. The cultural expectation is that this is normal and, unless you are getting an overwhelming number of these requests, that when asked, you will find time to socially connect.

I received a coffee chat request from Torsten Linz, the Senior Product Manager for the Source Code Management group, to chat about my comments and linking of a working example to an issue about code counting that he had become aware of. He also wanted to see if I could help get a copy of it working in his GitLab group.

During that collaborative time, I discovered that my example was not working because of some major code changes in SCC and because it presumed the GitLab group to be enumerated did not need the counting job to authenticate to prove that it should have access to the projects. While we were collaborating, we fixed these problems and improved the solution to use the SCC binary, rather than depend on working Golang runtimes. After our collaborative session, as I tweaked some more, I did parameter documentation in README.md and debugged the ability to run it either with a group enumeration or a provided list of specific git repos.

So I owe big thanks to Torsten and to GitLab’s cultural support for remote first water cooler conversations for improving this working example to the point that it is worth sharing with a broader audience. If you’d like to know more, check out the GitLab handbook page: Informal communication in an all-remote environment.