This blog post was originally published on the GitLab Unfiltered blog. It was reviewed and republished on 2021-05-05.

In a previous blog post called Small experiments, significant results I shared our recent success with conducting small experiments, but, in reality, we didn't start with the most iterative software development approach. It was the Growth team's early failures to iterate that helped us embrace launching smaller experiments with measurable results.

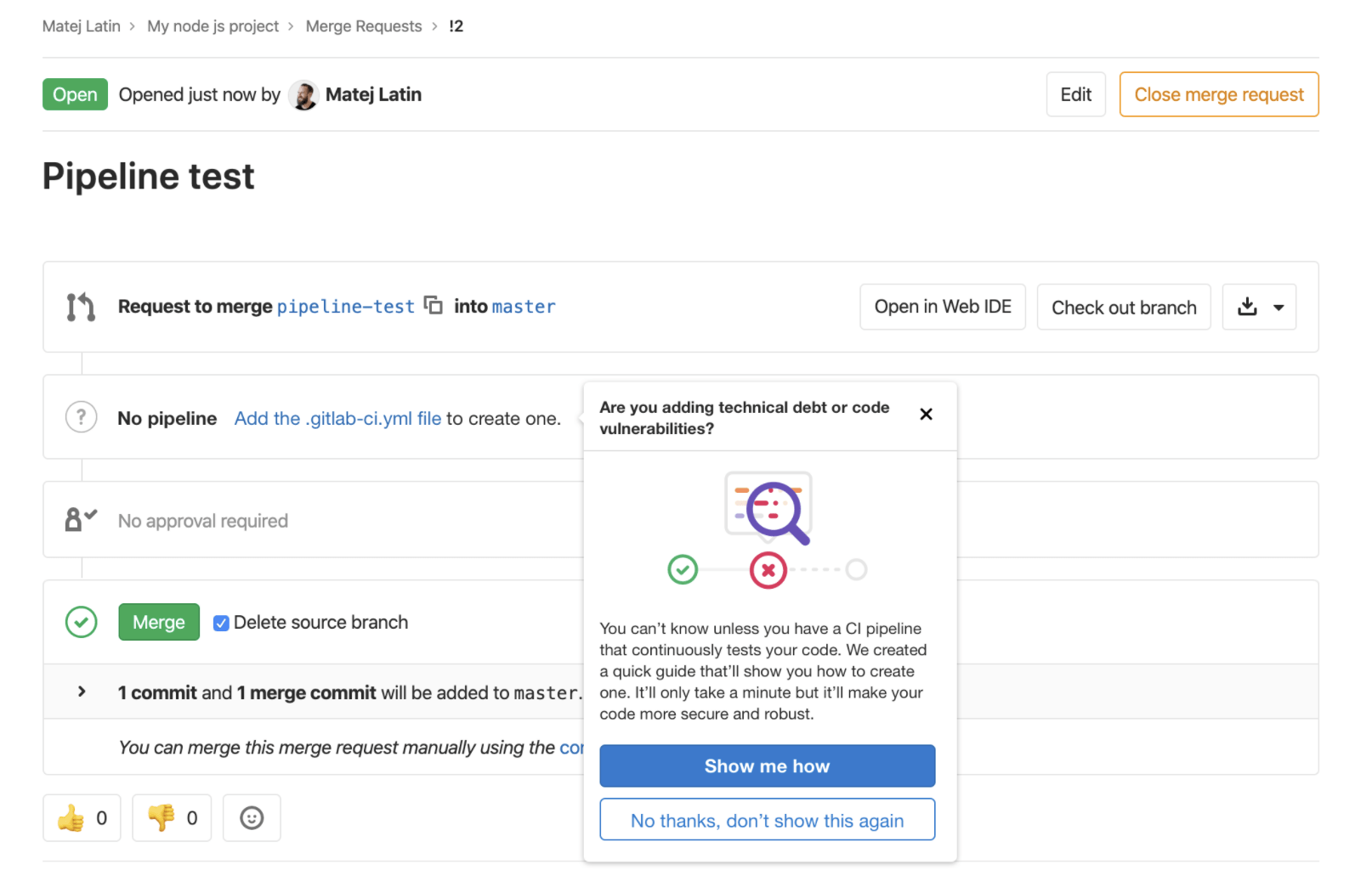

When the Growth team formed at GitLab in late 2019, we had little experience with designing, implementing, and shipping experiments intended to accelerate the growth of our user base. We hired experienced people but it was still hard to predict how long it would take to implement and ship an experiment. The "Suggest a pipeline" experiment was the first one I worked on with the Growth:Expansion team. The idea was simple: Guide users through our UI to help them set up a CI/CD pipeline.

The first iteration of the "suggest a pipeline" guided tour.

The first iteration of the "suggest a pipeline" guided tour.

See the original prototype of the "suggest a pipeline" guided tour.

The guided tour would start on the merge request page and ask the user if they want to learn how to set up a CI/CD pipeline. Those who opted in would be led through the three steps required to complete the setup. The team saw this as a simple three-step guide, so we committed ourselves to ship it without first considering if it was the smallest experiment we could complete. We wanted to create a guided tour because it hadn't been done yet at GitLab, but in the end, this wasn't the most iterative software development approach. Today, our thinking is: "What's the smallest thing we can test and learn from?"

One of GitLab's company values is iteration which means that we strive to do the smallest thing possible and get it out as quickly as possible. The concept of MVC (minimal viable change) guides this philosophy:

We encourage MVCs to be as small as possible. Always look to make the quickest change possible to improve the user's outcome.

While looking back, I realized we failed to embrace the MVC with the "suggest a pipeline" experiment, but I'm grateful for that mistake because it provided us with one of the most valuable lessons: Always strive to complete the smallest viable change first. The idea of iterative software development is valuable even, or maybe especially, with experiments.

Below are five reasons why it's important to break development down. Small iterations:

- Gets value to the user faster.

- Decreases the risk of shipping something that doesn't add value.

- Are easier to isolate and understand the impact of the changes.

- Ship faster so the team starts learning sooner.

- Allow teams to begin thinking about further iterations sooner or decide to abandon the experiment earlier (saving both time and resources).

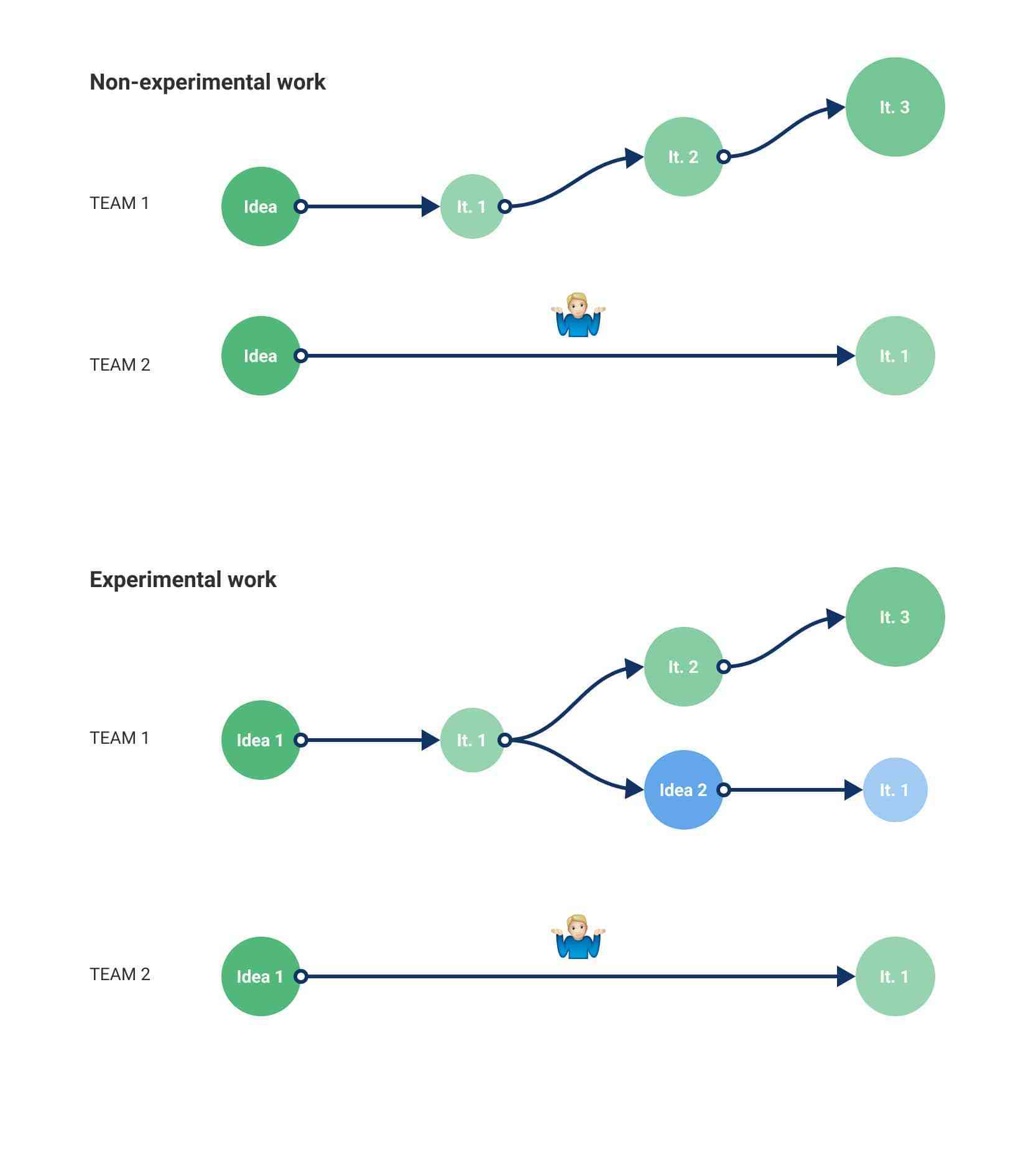

The power of iterative software development is clear by the two workflows.

The power of iterative software development is clear by the two workflows.

In the "non-experimental work" figure above, team one shipped a smaller iteration quickly and updated it twice, while team two only shipped one large iteration in the same time. Team one learned from their first small iteration and adapted their solution twice in the time team two shipped a larger iteration. It took team two longer to ship the large iteration and they sacrificed earlier findings they could have used to optimize their solution.

In the "experimental work" figure, team one shipped a smaller first iteration and reviewed early results, which helped them make an evidence-based decision as to iterate further on their first idea, or abandon it and move on to a new idea. Through this iterative software development process, they could either ship three iterations of their first idea or abandon it and start working on the first iteration of idea two. Team one could accomplish all this development in the same amount of time it took team 2 to ship a larger first iteration of idea one. Team one is much more likely to come to successful results and learnings faster than team two.

How the "suggest a pipeline" experiment should have been done

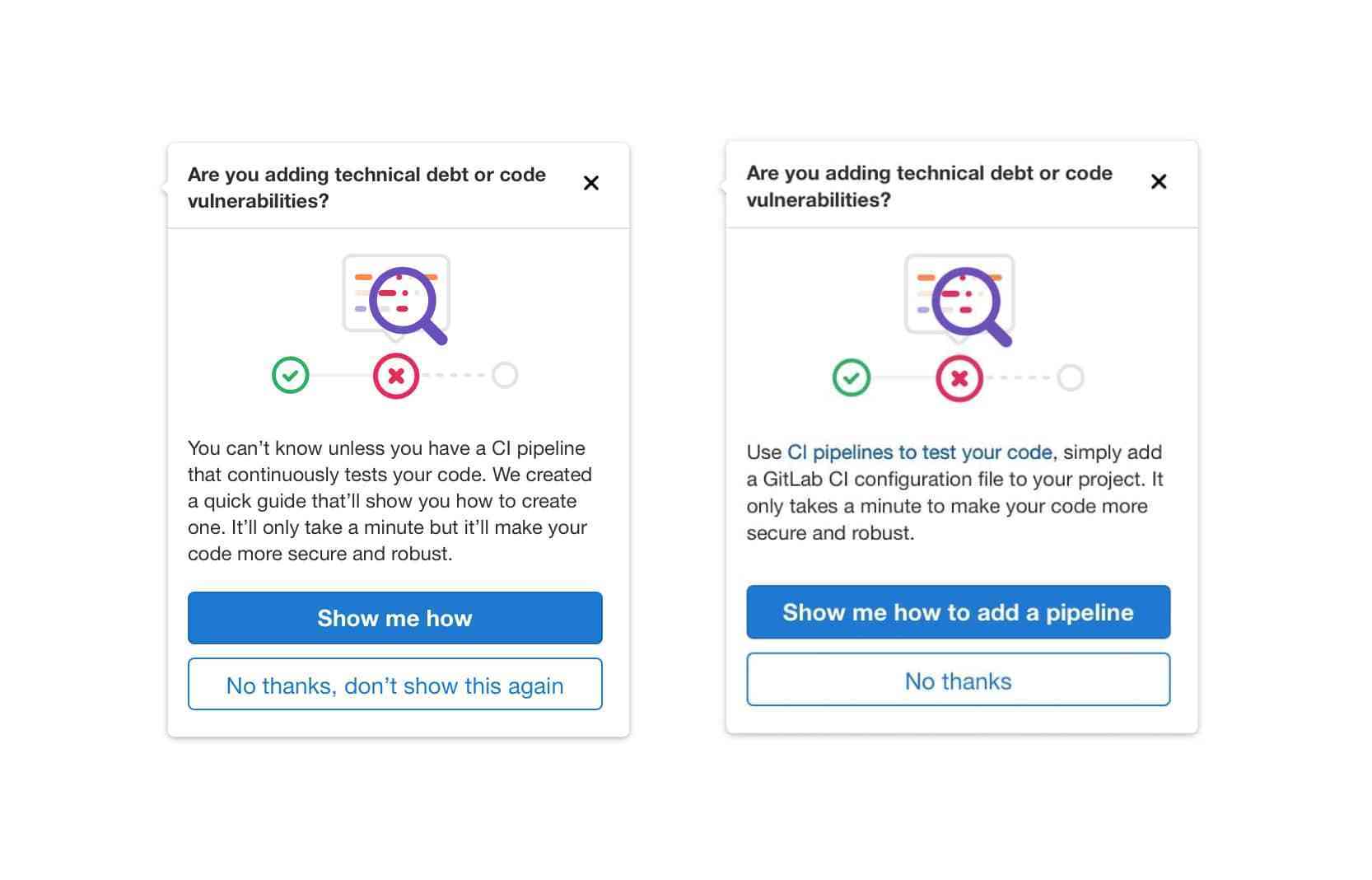

It's easy to reflect on our project today and see what we did wrong, but such reflection allows us to avoid repeating mistakes. The GitLab guided tour looked like a simple experiment to build and ship, but in the end it wasn't and took months to complete. Overall, the experiment was successful, but after it was implemented we took a second look and saw the project could be improved. We decided to implement some improvements by iterating on the copy in our first nudge to users to encourage more users to opt-in. Had we shipped a smaller experiment sooner, we could have iterated earlier and delivered an optimal version of the first nudge, allowing more users to benefit from the guided tour.

The second iteration of our opt-in copy is much stronger. Shipping a smaller iteration would have encouraged more users to opt-in to our experimental "guided tour" feature.

The second iteration of our opt-in copy is much stronger. Shipping a smaller iteration would have encouraged more users to opt-in to our experimental "guided tour" feature.

Because it took us months to complete the implementation of the experiment, it also took us months to iterate on it.

If I had to do a similar experiment now, I'd start much smaller, with something that could be built and shipped in less than a month, ideally even faster. For example, we could have shipped an iteration with that first nudge linking to an existing source that explains how to set up a pipeline. That would have enabled us to validate the placement of the nudge, its content, and its effectiveness. It would have significantly reduced the risk of the experiment.

Or maybe we could have shortened the guided tour to be just two steps, which is exactly what Kevin Comoli, product designer on Growth: Conversion, did. But because our idea already seemed like a small iteration, we never felt the urgency to reduce it further. So here's another reason why it's important to really think about the smallest possible iteration first: you can never be sure that what you're aiming to do will actually be as quick and simple as expected. So even when you think that your idea is the smallest possible iteration, think again.

How we're applying lessons on iteration to future experiments

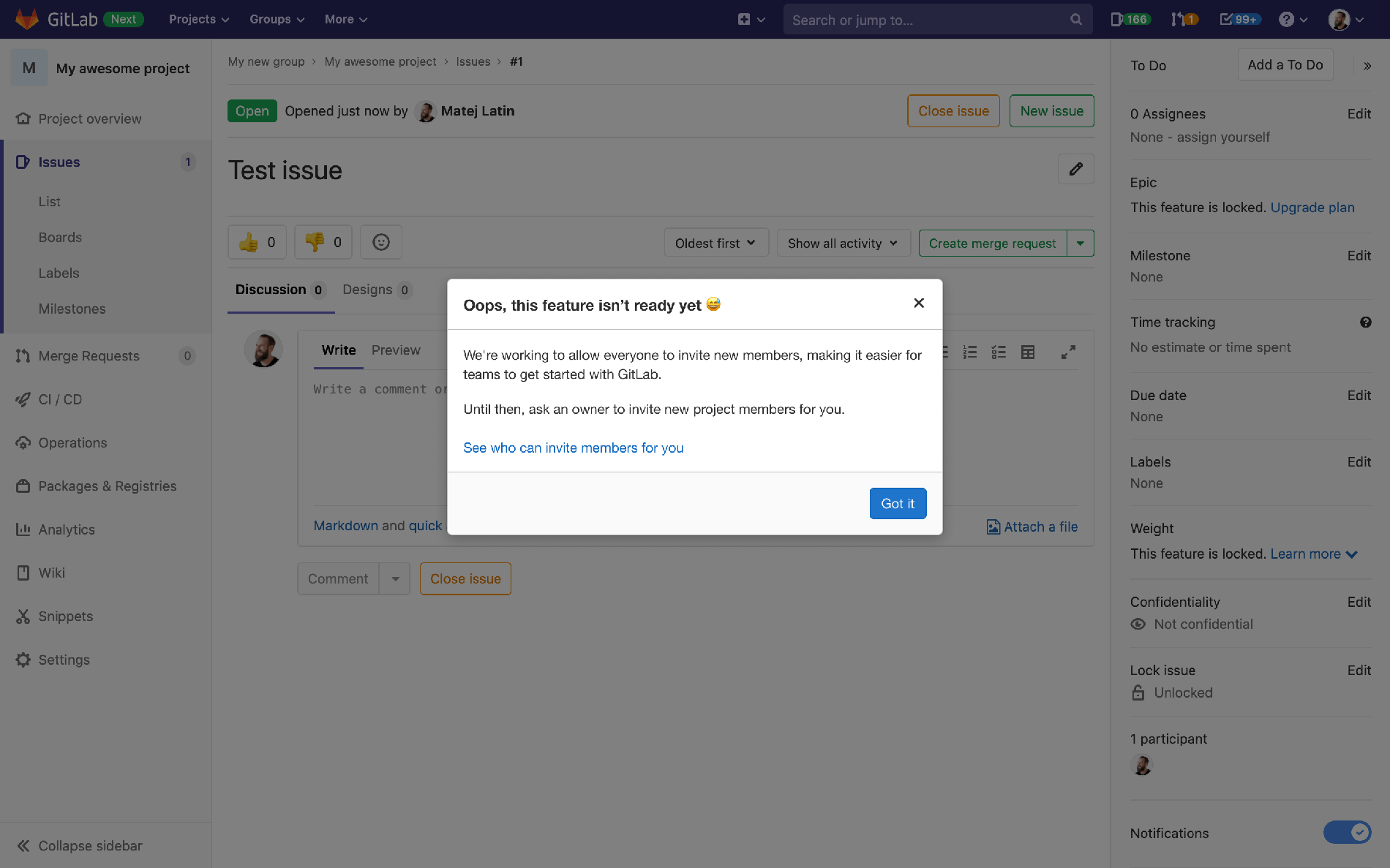

When I started working on the "invite members" experiment, my vision of how the experience should be was more complex than the "suggest a pipeline" guided tour experience. The idea behind the "invite members" experiment was that any user could invite their team members to a project and an admin user would have to approve the invitation. But because of our learnings from the pipeline tour we decided to simplify the first experiment. Instead of designing and building a whole experience, we decided to use a painted door test, which essentially means we are focusing on tracking the main call-to-action to gauge user interest. For the "invite members" experiment, the painted door test involved displaying an invite link that, once clicked, displayed a message to users that the feature wasn't ready and suggested a temporary solution. This allowed us to validate the riskiest part of the experiment: Do non-admin users even want to invite their colleagues?

The "invite members" painted door experiment involved displaying a modal showing that the feature wasn't ready yet, but helped us still gauge user interest in the feature before investing resources in developing the feature.

The "invite members" painted door experiment involved displaying a modal showing that the feature wasn't ready yet, but helped us still gauge user interest in the feature before investing resources in developing the feature.

Why iterative software development matters

We were lucky with the "suggest a pipeline" experiment. It was the first experiment we worked on, and it was "low hanging fruit", meaning it was a solution that required limited investment but still delivered big returns, which made the chance of failure lower. As we move away from obvious improvements and start exploring riskier experiments, we won't be able to rely on luck. We need to be diligent about iteration and break things down into MVCs and smaller experiments to reduce the risk of investing development time on projects that don't add value to the user experience, or fail to have a positive impact on GitLab's growth.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash