Published on: May 24, 2022

16 min read

When the pursuit of simplicity creates complexity in container-based CI pipelines

Simplicity always has a certain player in mind - learn how to avoid antipatterns by ensuring simplicity themes do not compromise your productivity by over-focusing on machine efficiencies.

In a GitLab book club, I recently read "The Laws of Simplicity," a great book on a topic that has deeply fascinated me for many years. The book contains an acronym that expresses simplicity generation approaches: SHE, which stands for "shrink, hide, embody." These three approaches for simplicity generation all share a common attribute: They are all creating illusions - not eliminations.

I've seen this illusion repeat across many, many realms of pursuit for many years. Even in human language, vocabulary development, jargon, and acronyms all simply encapsulate worlds of complexity that still exist, but can be more easily referenced in a compact form that performs SHE on the world of concepts.

Any illusion has a boundary or curtain where in front of the curtain the complexity can be dealt with by following simple rules, but, behind the curtain, the complexity must be managed by a stage manager.

For instance, when the magic show creates the spectre of sawing people in half, what appears to be a simple box is in fact an exceedingly elaborate contraption. Not only that, but the manufacturing process for an actual simple box and the sawing box are markedly different in terms of complexity. The manufacturing of complexity and its result are essentially the tradeoff for what would be the real-world complexity of actually sawing people in half and having them heal and stand up unharmed immediately afterward.

To bring this into the technical skills realm, consider that when you leverage a third-party component or API to add functionality, you only need to know the parameters to obtain the desired result. The people maintaining that component or API must know the quantum mechanics detail level of how to perform that work in a reliable and complete way.

Docker containers are a mechanism for embodying complexity, and are used in scaled applications and within container-based CI. When a CI/CD automation engineer uses container-based CI, it is possible to make things more complex and more expensive when attempting to do exactly the opposite.

At its core, this post is concerned with how it can happen that pursuing a simpler world through containers can turn into an antipattern - a reversal of desired outcomes - many times, without us noticing that the reversal is affecting our productivity. The prison of a paradigm is secure indeed.

The Second Law of Complexity Dynamics

Over the years I have come to believe that the pursuit of reducing complexity has similar characteristics to The Second Law of Thermodynamics. The net result of a change between mass and energy results in the the same net amount of mass and energy, but their ratio and form have changed. In what I will coin "The Second Law of Complexity Dynamics," complexity is similarly "conserved," it is just reformed.

If complexity is not eliminated by simplifying efforts, we reduce its impact in a given realm by changing the ratio of complexity and simplicity on each side of one or more curtains. But alas, complexity did not die, it just hid and is now someone else's management challenge. It is important not to think of this as cheating. There is no question that hiding complexity carries the potential for massive efficiency gains when the world behind the hiding mechanisms becomes the realm of specialty skills and specialists. When it truly externalizes the complexity management for one party, the world becomes more simple for that party.

However, the devil is in the details. If the hypothesis of "no net elimination of complexity" is correct, it is then important where the complexity migrates to. If it migrates to another part of the same process that must also be managed by the same people, then it may not result in a net gain of efficiency. If it migrates out of a previously embodied realm, then, in the pusuit of simplicity, we can actually reduce our overall efficiency when the process is considered as a whole.

Container-based CI pipelines as a useful case in point

I see the potential for efficiency reversals to crop up in my daily work time and again, and an interesting place where I've seen it lately is in the tradeoff of linking together hyper-specialized modules of code in containers for CI versus leveraging more generalized modules.

In creating container-based pipelines, I experience the potential for an efficiency reversal I have to consciously manage.

Containers make a simplicity tradeoff by design. They create a full runtime environment for a very single purpose but in doing so they strip back the container internals so far that general compute tasks are difficult inside them. If you step behind their "complexity embodying" curtain into the container, their simplistic environment can require more complex code to operate within.

In GitLab CI pipelines that utilize containers, all the scripts of jobs run inside the containers that are specified as their runtime environment. When one selects a specialized container - such as the alpine git container or the skopeo image management container - the code is subject to the limitations of the shell that container employs (if it has one at all).

Containers were devised to be hyper-specialized, purpose-specific runtimes that assure they can always run and run quickly for scaled applications. However, for many containers this means no shell or a very stripped back shell like busybox sh. It frequently also means not including the package manager for the underlying Linux distribution.

Time and again, I've found myself degrading the implementation of my shell code in key ways that make it more complex, so that it can run under these stripped back shells. In these cases, I do not benefit from the complexity hiding of newer versions of advanced shells like Bash v5. One of the areas is advanced Bash shell expansions, which embody a huge world of complex parsing and avoid a bunch of extraneous utilities. And another is advanced if and case statement comparison logic that processes regular expressions without external utilities and performs many other abstracted comparisons. There are many other areas of the language where this comes into play, but these two stand out.

So by having a simpler shell like busybox sh, the simplicities of advanced shell features become unhidden and join my side of the curtain. Now I have to manage them in my code. But then, guess what? No package manager means the inability to install other Linux utilities and languages extensions that I could also employ to push that same complexity back out of my space. And, of course, it means installing Bash v5 would be difficult as well.

So the simplicity proposition of a tightly optimized purpose-specific container can reverse the purported efficiency gains in the very important realm of the code I have to write. It also means I frequently have to break up my code into multiple jobs to utilize the specializations of these containers in a sequence or to transport the results of a specialized container into a fuller coding environment. This increases the complexity of the pipeline as I now have to pass artifacts and variable data from one job to another with a host of additional YAML directives, and sometimes deploy infrastructure (e.g., Runner caching).

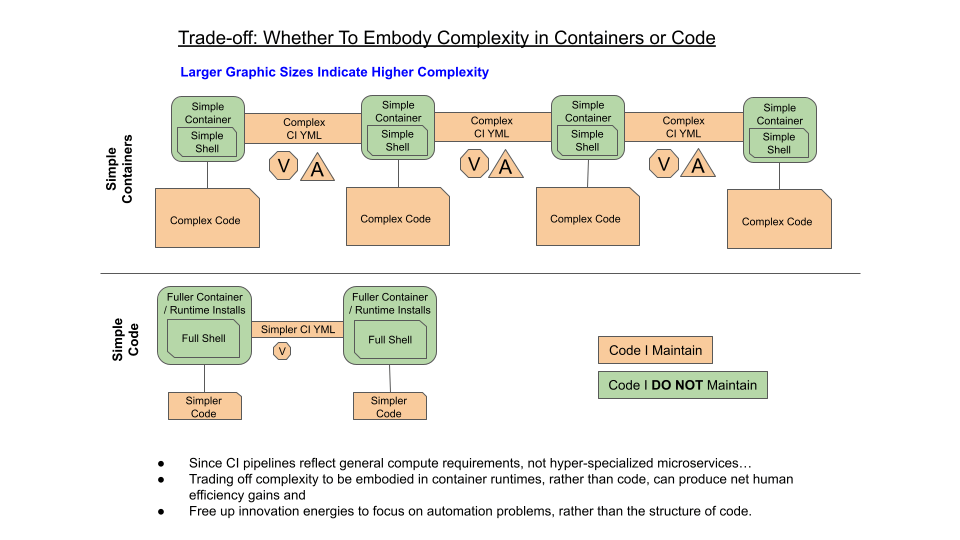

In the case of CI using containers, when the simplicity tradeoffs move complexity to things I do not maintain, such as base containers, operating system packages, and full shell environments, into things I do maintain, such as CI YAML and Shell Script code, then I am also inheriting long-term complexity maintenance. In the cloud, we know this as undifferentiated heavy lifting.

Interestingly, the proliferation of specialized containers can also require more machine resources and can lengthen processing time as containers are retrieved from registries and loaded and artifacts and source code are copied in and out of each job-based container.

Simplicity target: Efficiency

It's easy to lose sight of the amount of human effort and ingenuity being applied to knowing and managing the coding structure, rather than being applied to solving the real automation problems of the CI pipeline. The net complexity of the pipeline can also mean it is hard to maintain an understanding of it even if you are working in it every day - and for newcomers onboarding, it can be many weeks before they fully understand how the system works.

Of course, I can create my own containers for CI pipelines, but now I've added the complexity of container development and continuous updates of the same in order for my pipeline code to be operational and stay healthy. I am still behind the curtain for that container. For teams whose software is not itself containerized, the prospect of learning to build containers just for CI can create a lot of understandable friction to adopting a container-based CI development process. This friction may be unnecessary if we make a key heuristic adaptation.

Walking the tightwire above the curtain

So how do I manage the tensions of these multiple worlds of complexity when it comes to container-based pipelines to try to avoid efficiency reversals in the net complexity of the pipeline?

It is simple. I will describe the method and then the key misapplied heuristic and how to adjust it.

-

I hold that the primary benefits of container-based CI are a) dependency isolation by job (so that you don’t have a massive and brittle CI build machine specification to handle all possible build requirements), and b) clean CI build agent state by obtaining a clean container copy for each job. These benefits do not imply having to abide by microservices container resource planning and doing so is what creates an antipattern in my productivity.

-

I frequently use a Bash 5 container (version pegged if need be) where all the complexity that advanced shell capabilities embody for me stay behind the curtain.

-

Instead of running a hyper-minimalized container for a given utility, I do a runtime install of that utility (gasp!) in a container that has my rich shell. I utilize version pegging during the install if I feel version safety is paramount on the utility. Alternatively, if a very desirable runtime of some type is difficult to setup and does not have a package, I look for a container that has a package manager that matches a packaged version of the runtime and also allows me to install my advanced scripting language if needed.

-

If, and only if, the net time of the needed runtime installs exceeds the net pipeline time to load a string of specialized containers (with artifact handling) plus my time to develop and manage a pipeline dependency in the form of a custom container, then do I consider possibly creating a pipeline specific container.

-

Through this process a balancing principle also emerges. Since I have been doing runtime installs as a development practice, I have actually already MVPed what a pipeline specific container would need to have installed. I can literally copy the installation lines into a Docker file if I wish. I can also notice if I have commonality across multiple pipelines where it makes sense to create a multi-pipeline utility container.

In a recent project, following these principles caused me to avoid the skopeo container and instead install it on the Bash 5 container using a package manager.

If your team is big into Python or PowerShell as your CI language, it would make sense to start with recent releases of those containers. The point is not advanced Bash -but an advanced version of your general CI scripting language that prevents you from creating work arounds in your code for problems that are well-solved in publicly available runtimes.

Keep in mind that this adjustment is very, very focused on containers in CI pipelines, which, by nature, reflect general compute processing requirements where many vastly different operations are required in a pipeline. I am not advocating this approach for true microservices applications where, by design, a given service has very defined purpose and characteristics and, at scale, massively benefits from the machine efficiency of hyper-minimalized, purpose-specific granularity.

Misapplied heuristics

Frequently when a pattern has an inflection point at which it becomes an antipattern, it is due to misapplying the heuristics of the wrong realm. In this case, I believe, that normal containerization patterns for microservices apps are well founded, but they apply narrowly to "engineered hyper-specialized compute" of a granule we call "a microservice" (note the word "micro" applies to the scope of compute activities). Importantly, they apply because the process itself is designed as hyper-specialized around a very specific task. The container contents (included dependencies), immutability principle (no runtime change), and the runtime compute resources can be managed exceedingly minimally because of the small and highly specific scope of computing activities that occur within the process.

This is essentially the embodiment of the 12 Factor App principle called “VIII. Concurrency,” which asserts that scaling should be horizontal scaling of the same minimalized process, not vertical scaling of compute resources inside a given process. If the system experiences 10x work for a particular activity, we create 10 processes, we do not request 10x memory and 10x CPU within one running process. Microservices architecture tightly controls the amount of work in each request so that it is hyper-predictable in its compute resource requirements and, therefore, scalable by adding identical processes.

CI compute, by nature, is the opposite of hyper-specialized. Across build, test, package, deploy, etc., etc., there are many huge variations in required machine resources of memory, CPU, network I/O and high-speed disk access and, importantly, included dependencies. The generalized compute nature also occurs due to varying inputs so the same defined process might need a lot more resources due to the nature of the raw input data. For example, varying input volume (e.g. a lot versus few data items) or varying input density (e.g. processing binary files versus text files).

It is the process that is being containerized that holds the attribute of generalized compute (bursty on at least some compute resources) or hyper-specialized (narrow definition of work to be done and therefore well-known compute resources per unit of completed work). Containerizing a process that exhibits generalized compute requirements is useful, but planning the resources of that container as if containerizing it has transformed the compute requirements into hyper-minimalized is the inflection point at which it becomes an antipattern, actually eroding the sought-after benefits we set out to create.

In the model I employ for leveraging containers in CI, the loosening of the hyper-specialization, immutablility (no-runtime installs), and very narrow compute resources principles of microservices simply reflects the real world in that CI compute as a whole exhibits the nature of generalized, not hyper-specialized, compute characteristics.

Another realm where this seems true is desired state configuration management technologies - also known as “Configuration as Code”. It is super simple if there are pre-existing components or recipes for all that you need to do but as soon as you have to build some for yourself, you enter a world of creating imperative code against a declarative API boundary (there's the "embodiment" curtain - the declarative API boundary). Generally, if you have not had to implement imperative code to process declaratively, this new world takes some significant experience to become proficient.

Iterating SA: Experimental improvements for your next project

-

In general, favor simplicity boundaries that reduce your work, especially in the realm of undifferentiated heavy lifting. In the realm of container-based CI, this includes having a rich coding language and a package manager to acquire additional complexity embodying utilities quickly and easily.

-

In general, be suspicious of an underlying antipattern if you have to spend an inordinate amount of time coding and maintaining workarounds in the service of simplicity. In the realm of container-based CI, this would be containers that are ultra-minimalized around microservices performance characteristics when they don’t hyper-scale as a standing service within CI.

-

In general, stand back and examine the net complexity of the code and frameworks that will have to be maintained by yourself or your team and check if you’ve made tradeoffs that have a net negative tax on your efficiency. When complexity that can be managed by machines enters your workspace at high frequency, then you have a massive antipattern of human efficiency.

-

It is frequent that when the hueristics being applied create negative human efficiency they also create negative machine efficiency. Watch for this effect in your projects. The diagram in the post shows that over-minimalized containers can easily lead to using a lot more of them - all of which has machine overhead as well.

If the above resonates, CI pipeline engineers might want to consider loosening the "microservices" heuristics of hyper-specialization, ultra-minimalization, and immutability (no dynamic installs) for CI pipeline containers in order to ensure that the true net complexity level of the code they have to maintain is in balance and their productivity is preserved.

Appendix: Working examples of this idea

-

AWS CLI Tools in Containers has both Bash and PowerShell Core (on Linux OS) available so that one container set can suit the automation shell preference of both Linux and Windows heritage CI automation engineers.

-

CI file installs yq dynamically in the Bash container, but then only installs the heavier jq and skopeo if needed by the work implied, which demonstrates a way to be more efficient even when runtime installs are desired.

-

Bash and PowerShell Script Code Libraries in Pure GitLab CI YAML shows how to have libraries of CI script code available to every container in a pipeline without encapsulating the libraries in a container themselves and with minimalized CI YAML complexity compared to YAML anchors, references, or extends. While the method is a little bit challenging to setup, from then on out it pays back by decoupling scripting libraries from any other pipeline artifact.

-

CI/CD Extension Freemarker File Templating shows the install is very quick and only affects one job and still version pegs the installed utility.