Published on: September 2, 2021

12 min read

What we learned about configuring Sidekiq from GitLab.com

Sidekiq is a key part of GitLab, and usually works well out-of-the-box, but sometimes it needs more attention at scale.

Sidekiq in GitLab works perfectly well out-of-the-box in most use cases, but it requires a little more attention in larger deployments or other specialized cases. We've learned a lot about how to configure Sidekiq in large deployments by maintaining GitLab.com – one of the largest instances of GitLab in existence. We added some critical features to GitLab.com in the past year to make it easier to configure Sidekiq in a manner more consistent with the maintainer's guidance, having strayed from this path for some time.

We are publishing two blog posts devoted to this topic. In this first post, we will unpack how we configured Sidekiq for GitLab.com, and in our second post, we will explain how to apply this to your GitLab instance.

[Learn more about how we iterated on Sidekiq background jobs]

We built on that work and the learnings for the project we describe in a blog post on Sidekiq background jobs.

What is Sidekiq?

Sidekiq is usually the background job processor of choice for Ruby-on-Rails, and uses Redis as a data store for the job queues. Background (or asynchronous) job processing is critical to GitLab because there are many tasks that:

- Shouldn't tie up relatively expensive HTTP workers to perform long-running operations

- Do not operate within an HTTP-request context (e.g., scheduled/periodic tasks)

For most users, how Sidekiq uses Redis doesn't matter much – Sidekiq receives a Redis connection and magic ensues, but at larger scales it becomes important.

The Redis data structure that Sidekiq uses for queues is a LIST which is literally an ordered sequence of entries. For Sidekiq, each entry is some JSON which describes the work to do (Ruby class + arguments) and some metadata. Out-of-the-box Sidekiq uses a single queue named "default," but it's possible to create and use any number of other named queues if there is at least one Sidekiq worker configured to look at every queue. Jobs are enqueued at the end of the list using RPUSH, and are retrieved for execution from the front of the list with BRPOP.

A key fact is that BRPOP is a blocking operation – a Sidekiq worker looking to perform work will issue and be blocked by a single BRPOP until any work is available or a timeout (2-second default) is exceeded. Redis then returns the job (if available) and removes it from the LIST.

About Concurrency (threading)

This is a little bit tangential, but is a important later, so bear with me (or skip this section and come back to it later if you really need it).

When starting Sidekiq you can tell it how many threads to run, and where each thread request works from Redis and can potentially be executing a job. Sounds like an easy way to allow Sidekiq to do more work, right? Well, not exactly, because threading in Ruby is subject to the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). For more, read this great explanation about threading, from which I will quote one key statement:

This means that no matter how many threads you spawn, and how many cores you have at your disposal, MRI will literally never be executing Ruby code in multiple threads concurrently

So each Sidekiq worker process will – at best – only occupy one CPU. Threading is about avoiding constraints on throughput from blocking I/O (mostly network, like Web requests or DB queries).

The default concurrency is 25, which is fine for a default GitLab installation on a single node with a single Sidekiq worker and a wide mix of jobs. But if the jobs are mostly CPU-bound (doing heavy CPU computation in Ruby) then 25 may be far too high and counter-productive as threads compete for the GIL. Or, if your workload is heavily network dependent, a higher number might be acceptable since most of the time is spent waiting.

Why does this matter? When you start splitting up (sharding) your Sidekiq fleet, you need to pay attention to what concurrency you give to each shard to ensure it is compatible with the subset of Sidekiq jobs that will be executing here.

How we configured Sidekiq on GitLab.com

How we historically used Sidekiq

Some time ago in GitLab history, we decided to use one Sidekiq queue per worker (class), with the name of the queue automatically derived from the class (name + metadata), e.g., the class WebHookWorker runs in the web_hook queue. This approach has some benefits, but the author of Sidekiq does not recommend having more than a "handful" of queues per Sidekiq process.

I assume handful means around 10 queues. At the time, we had about 45 job classes/queues which was beyond a "handful" but not excessively so. However, as the GitLab code base has grown, we've added more job classes and queues. Currently, we have 440, and more will inevitably be added as new features are added. As discussed in the previous blog post, we split our Sidekiq worker fleet into multiple shards with different collections of jobs on each shard, based on the job resource requirements and impact on user experience.

However, our "catchall" shard is still responsible for roughly 300 of those workers/queues. So each time a catchall Sidekiq worker requests the next available job, it issues a BRPOP with a huge list of queues. Redis then needs to parse that request, set up internal data structures for each queue, find the next available job, and then tear down those data structures. That's a lot of overhead just to fetch one job. We knew this was going to be a problem eventually, but for a while we were able to put our effort into other areas.

How we configured Sidekiq on GitLab.com today

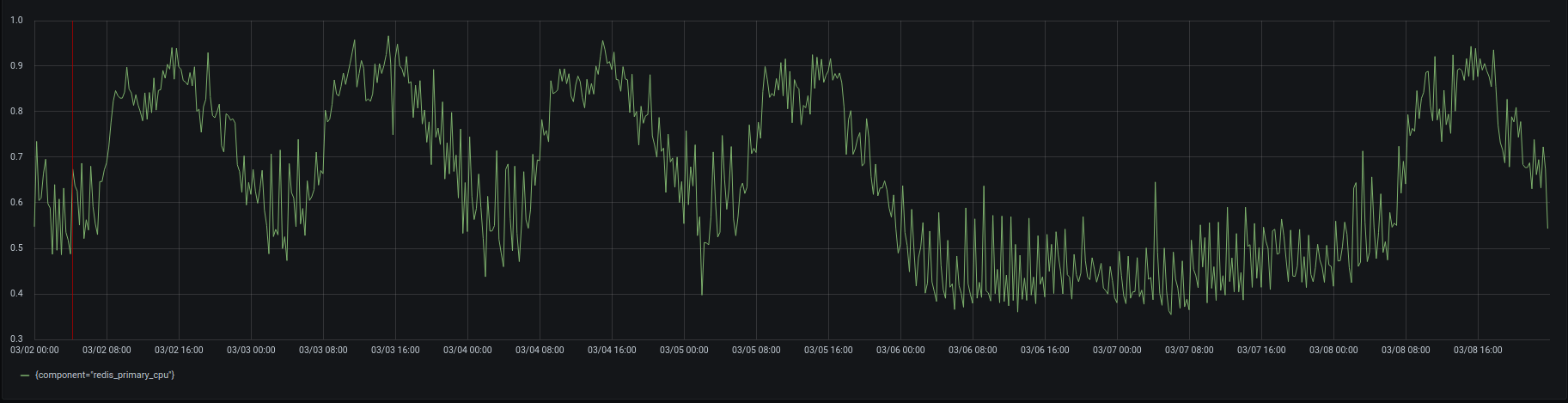

By early-to-mid 2021, the Redis instance dedicated to Sidekiq was starting to hit more than 95% CPU saturation at peak:

What it looks like when Redis CPU usage reaches 95%

What it looks like when Redis CPU usage reaches 95%

Redis is fundamentally single-threaded. Sure, IO Threads in version 6 changes that a bit, but command execution is serialized through the core thread, so once utilization hits 100% of a CPU core, it doesn't matter how many other idle/spare CPUs you have.

In my opinion, Redis is an absolutely amazing bit of software – the documentation is excellent, it is more robust than we deserve, and the throughput is spectacular on a single core. It has carried us a long way, but there is this hard limit that we cannot pass.

If we do exceed these limits, Sidekiq work will not be dispatched fast enough at peak times, and things will go wrong – possibly in quite subtle and troublesome ways. Last year, we gained a lot of headroom by upgrading to the latest CPUs in GCP, but that's not repeatable and merely put off the inevitable. BRPOP with many queues is the core reason for this saturation with all that overhead on every request from thousands of Sidekiq workers. So what else could we do?

As we understand it, the CPU usage is generated by a combination of the number of queues and the number of workers listening to those queues for work, so we had two possible paths ahead of us:

- Reduce the number of workers using a given Redis by splitting Sidekiq into multiple fleets

- Keep a single logical fleet and reduce the number of queues

Both were plausible options for reducing Redis CPU usage, but didn't overlap in implementation, and had quite distinct challenges.

We needed more data in order to make the best choice. We performed some experiments by spending a few days creating an artificial test harness that produced and consumed Sidekiq jobs at volumes mimicking what we see on GitLab.com. I cannot emphasize enough how artificial the workload is, and although we added some complexity to replicate certain aspects of production, it will never be the same as the real workload on GitLab.com. It did show that reducing the number of queues to "one queue per shard" had the greatest effect. Other discussions also concluded this approach was likely safer, so the decision was easy to make.

If you're interested, the code for those experiments is available here, but fair warning, it is just enough to do what we needed to do, and requires some manual setup.

How we adjusted the Sidekiq routing rules

This change would move us away from the one-queue-per-worker paradigm, but we still need to maintain the current sharding configuration on GitLab.com in particular, so our Sidekiq configuration is a fine balance of queues and workers and we cannot throw that all away. So we picked up work from last year, adjusted the plan slightly, and implemented Sidekiq routing rules.

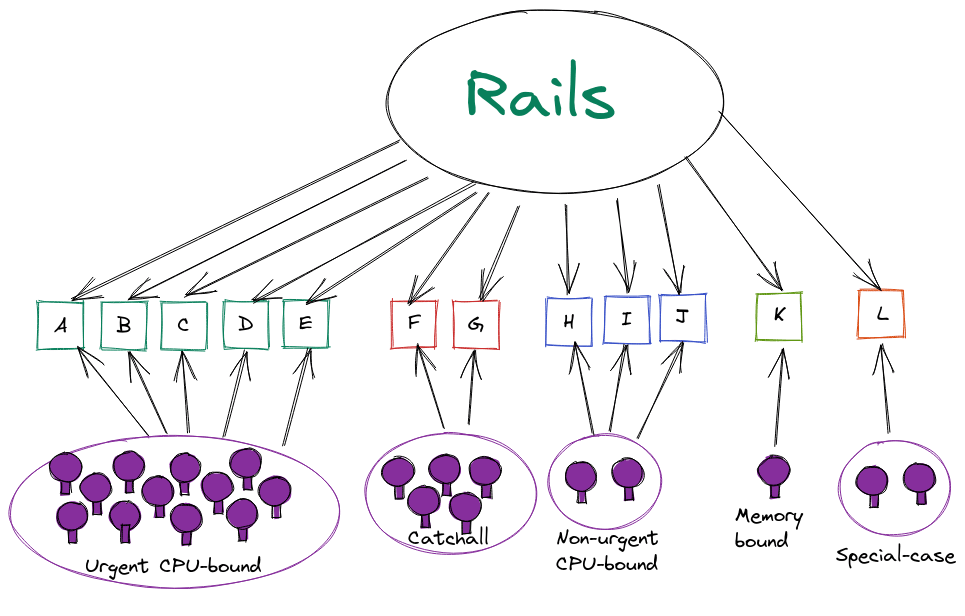

Prior to routing rules, the decision on where a job ran was made by the Sidekiq workers. The image below will help you visualize the process:

Representation of Sidekiq job routing with one queue per worker

Representation of Sidekiq job routing with one queue per worker

In the image above, each lettered-box represents a queue, and jobs are scheduled into a queue based on their name. Where they execute is up to the workers. As you might imagine, it's entirely possible for Rails to put work into a queue that no worker is configured to pick up. With more than 400 workers that's far too easy, so for GitLab.com we ensured that didn't happen by using queue-selector expressions for most shards and the negate option to define our catchall (default) shard with some scripts to make that easier. It was still a complex process and migrating to Kubernetes added challenges for the final catchall shard as we dealt with the last NFS dependencies and had workloads running in VMs and Kubernetes.

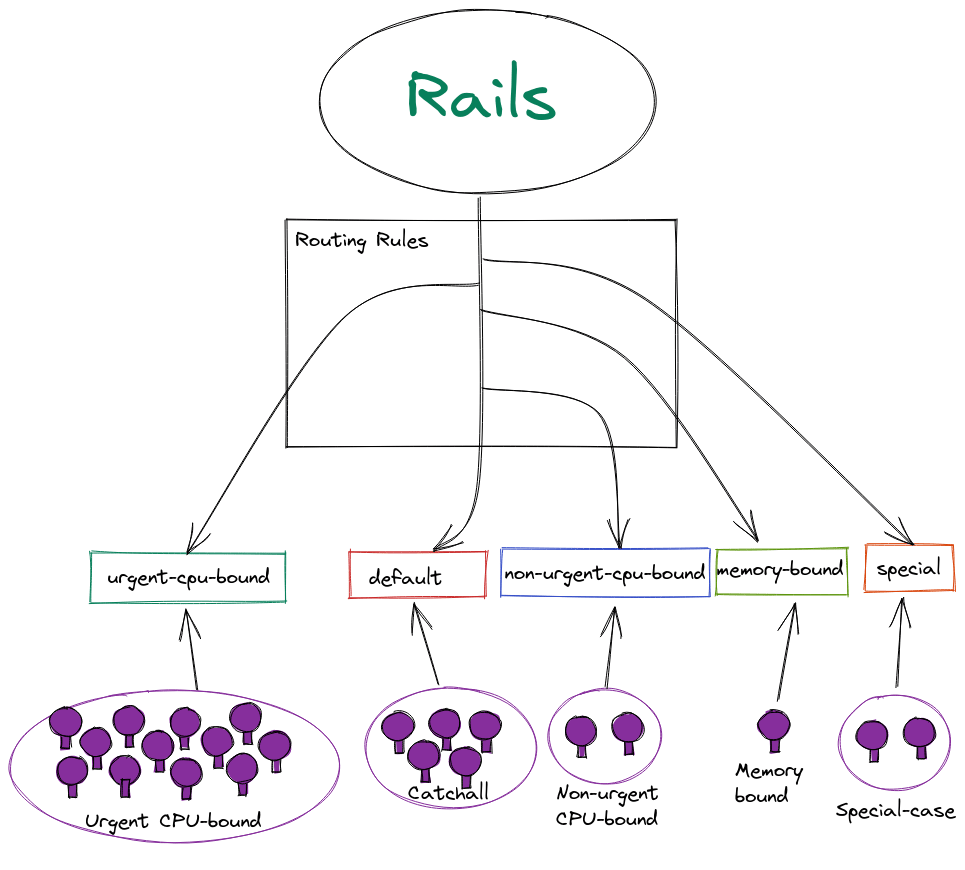

With routing rules the decision for which workload should pick up a given job is made when the job is enqueued. The image below should make it easier to understand this process.

Representation of Sidekiq job routing with routing rules

Representation of Sidekiq job routing with routing rules

Routing rules use the same queue-selector syntax, so the same expressions can still be used to represent shards as before. But because the routing rules are an ordered set of rules applied in the same way for every job no matter where it's scheduled from, we no longer need to use a complex generated "negate" expression to define the catchall/default shard.

Instead, all that is required is a final "default" rule (*) that matches all remaining jobs and routes them to the catchall shard (we use the default queue for that out of convenience). We only need to ensure there is a set of Sidekiq workers listening for each of the resulting small number of simply named queues that we can base on the shard name for obviousness and simplicity. This is much easier to get right and visually verify.

Learn more about the routing rules syntax and how to configure them.

How it's going

Over the past few months we've been working on migrating GitLab.com to this new arrangement for the catchall shard. When it came to actually switching to routing rules we took a measured approach and did it in phases.

We started by creating a set of routing rules that recreated our existing shards, but with the 'nil' target, which tells Rails to keep using the per-worker queue. This gave us a base from which we could maintain existing behavior but then start routing to a limited named queues in simple iterative steps.

From there, we could add new rules immediately before the final catchall rule to the default queue, which GitLab doesn't actively use out-of-the-box, but which the catchall shard listens to. First, we added some rules that don't normally run on GitLab.com, but which we could use to test (e.g., Chaos::SleepWorker).

Next, we moved a feature category with a couple of jobs, first routing them to default then we stopped listening to them in the catchall shard.

We repeated this pattern of rerouting then not listening in batches using Feature Categories as a relatively simple way to select groups of related workers. After selecting the groups, we built them up from batches with small groups of low-use categories with lots of classes but not many jobs per second to single feature categories at the end. Continuous_integration (18% of catchall shard jobs) and integrations and source_code_management` are each generating about 30% of catch-all shard jobs. We gained confidence in the queue-handling as this progressed, and gave ourselves plenty of opportunity to gather data and pause if necessary.

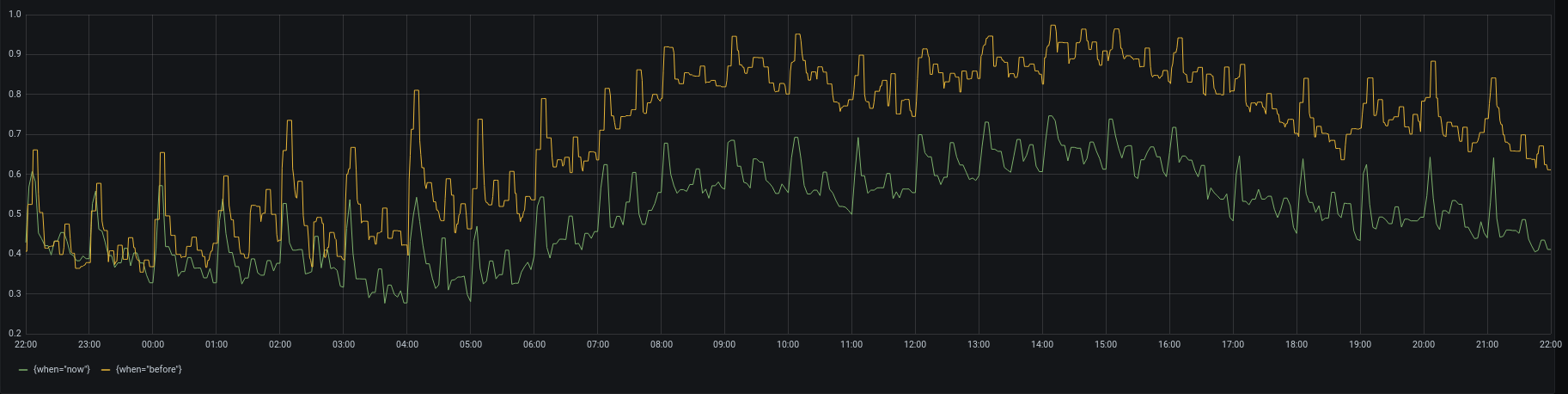

At each stage we stopped listening to several 10s of queues from our catchall Kubernetes deployment, and gradually saw the CPU saturation on Redis drop. After finally shutting down Sidekiq on our (now legacy) virtual machines, we've reached a final state where at peak times CPU on Redis reaches only around 75%, down from peaks of 95% or higher:

Reduced CPU usage in Redis

Reduced CPU usage in Redis

What will we do next?

First, we need to finish the one-queue-per-shard migration for all the other shards, aside from catchall. These shards won't have the same level of impact because they run far fewer queues than catchall, but will lead to a consistent job routing strategy. In the long term, Redis will eventually become the bottleneck again, and we're going to have to either split Sidekiq into multiple fleets, or change to something architecturally different. Multiple fleets has some challenges, but means we can keep using the existing technologies we have invested time and tooling in (including Omnibus for self-managed deployments). But given the bottleneck is still eventually going to be Redis CPU, this might well be the time to look at other job processing paradigms.

In our next blog post, we explain how you can take what we learned about configuring Sidekiq for GitLab.com and apply it to your own large instance of GitLab.

Cover image by Jerry Zhang on Unsplash