Published on: October 2, 2017

18 min read

Scaling the GitLab database

An in-depth look at the challenges faced when scaling the GitLab database and the solutions we applied to help solve the problems with our database setup.

For a long time GitLab.com used a single PostgreSQL database server and a single replica for disaster recovery purposes. This worked reasonably well for the first few years of GitLab.com's existence, but over time we began seeing more and more problems with this setup. In this article we'll take a look at what we did to help solve these problems for both GitLab.com and self-managed GitLab instances.

For example, the database was under constant pressure, with CPU utilization hovering around 70 percent almost all the time. Not because we used all available resources in the best way possible, but because we were bombarding the server with too many (badly optimized) queries. We realized we needed a better setup that would allow us to balance the load and make GitLab.com more resilient to any problems that may occur on the primary database server.

When tackling these problems using PostgreSQL there are essentially four techniques you can apply:

- Optimize your application code so the queries are more efficient (and ideally use fewer resources).

- Use a connection pooler to reduce the number of database connections (and associated resources) necessary.

- Balance the load across multiple database servers.

- Shard your database.

Optimizing the application code is something we have been working on actively for the past two years, but it's not a final solution. Even if you improve performance, when traffic also increases you may still need to apply the other two techniques. For the sake of this article we'll skip over this particular subject and instead focus on the other techniques.

Connection pooling

In PostgreSQL a connection is handled by starting an OS process which in turn needs a number of resources. The more connections (and thus processes), the more resources your database will use. PostgreSQL also enforces a maximum number of connections as defined in the [max_connections]max-connections setting. Once you hit this limit PostgreSQL will reject new connections. Such a setup can be illustrated using the following diagram:

Here our clients connect directly to PostgreSQL, thus requiring one connection per client.

By pooling connections we can have multiple client-side connections reuse

PostgreSQL connections. For example, without pooling we'd need 100 PostgreSQL connections to handle 100 client connections; with connection pooling we may only need 10 or so PostgreSQL connections depending on our configuration. This means our connection diagram will instead look something like the following:

Here we show an example where four clients connect to pgbouncer but instead of using four PostgreSQL connections we only need two of them.

For PostgreSQL there are two connection poolers that are most commonly used:

- [pgbouncer]pgbouncer

- [pgpool-II]pgpool

pgpool is a bit special because it does much more than just connection pooling:

it has a built-in query caching mechanism, can balance load across multiple databases, manage replication, and more.

On the other hand pgbouncer is much simpler: all it does is connection pooling.

Database load balancing

Load balancing on the database level is typically done by making use of

PostgreSQL's "[hot standby]hot-standby" feature. A hot-standby is a PostgreSQL replica that allows you to run read-only SQL queries, contrary to a regular standby that does not allow any SQL queries to be executed. To balance load you'd set up one or more hot-standby servers and somehow balance read-only queries across these hosts while sending all other operations to the primary.

Scaling such a setup is fairly easy: simply add more hot-standby servers (if necessary) as your read-only traffic increases.

Another benefit of this approach is having a more resilient database cluster.

Web requests that only use a secondary can continue to operate even if the primary server is experiencing issues; though of course you may still run into errors should those requests end up using the primary.

This approach however can be quite difficult to implement. For example, explicit transactions must be executed on the primary since they may contain writes.

Furthermore, after a write we want to continue using the primary for a little while because the changes may not yet be available on the hot-standby servers when using asynchronous replication.

Sharding

Sharding is the act of horizontally partitioning your data. This means that data resides on specific servers and is retrieved using a shard key. For example, you may partition data per project and use the project ID as the shard key. Sharding a database is interesting when you have a very high write load (as there's no other easy way of balancing writes other than perhaps a multi-master setup), or when you have a lot of data and you can no longer store it in a conventional manner (e.g. you simply can't fit it all on a single disk).

Unfortunately the process of setting up a sharded database is a massive undertaking, even when using software such as [Citus]citus. Not only do you need to set up the infrastructure (which varies in complexity depending on whether you run it yourself or use a hosted solution), but you also need to adjust large portions of your application to support sharding.

Cases against sharding

On GitLab.com the write load is typically very low, with most of the database queries being read-only queries. In very exceptional cases we may spike to 1500 tuple writes per second, but most of the time we barely make it past 200 tuple writes per second. On the other hand we can easily read up to 10 million tuples per second on any given secondary.

Storage-wise, we also don't use that much data: only about 800 GB. A large portion of this data is data that is being migrated in the background. Once those migrations are done we expect our database to shrink in size quite a bit.

Then there's the amount of work required to adjust the application so all queries use the right shard keys. While quite a few of our queries usually include a project ID which we could use as a shard key, there are also many queries where this isn't the case. Sharding would also affect the process of contributing changes to GitLab as every contributor would now have to make sure a shard key is present in their queries.

Finally, there is the infrastructure that's necessary to make all of this work.

Servers have to be set up, monitoring has to be added, engineers have to be trained so they are familiar with this new setup, the list goes on. While hosted solutions may remove the need for managing your own servers it doesn't solve all problems. Engineers still have to be trained and (most likely very expensive)

bills have to be paid. At GitLab we also highly prefer to ship the tools we need so the community can make use of them. This means that if we were going to shard the database we'd have to ship it (or at least parts of it) in our Omnibus packages. The only way you can make sure something you ship works is by running it yourself, meaning we wouldn't be able to use a hosted solution.

Ultimately we decided against sharding the database because we felt it was an expensive, time-consuming, and complex solution to a problem we do not have.

Connection pooling for GitLab

For connection pooling we had two main requirements:

- It has to work well (obviously).

- It has to be easy to ship in our Omnibus packages so our users can also take advantage of the connection pooler.

Reviewing the two solutions (pgpool and pgbouncer) was done in two steps:

- Perform various technical tests (does it work, how easy is it to configure, etc).

- Find out what the experiences are of other users of the solution, what problems they ran into and how they dealt with them, etc.

pgpool was the first solution we looked into, mostly because it seemed quite attractive based on all the features it offered. Some of the data from our tests can be found in [this]pgpool-comment-data comment.

Ultimately we decided against using pgpool based on a number of factors. For example, pgpool does not support sticky connections. This is problematic when performing a write and (trying to) display the results right away. Imagine creating an issue and being redirected to the page, only to run into an HTTP 404 error because the server used for any read-only queries did not yet have the data. One way to work around this would be to use synchronous replication, but this brings many other problems to the table; problems we prefer to avoid.

Another problem is that pgpool's load balancing logic is decoupled from your application and operates by parsing SQL queries and sending them to the right server. Because this happens outside of your application you have very little control over which query runs where. This may actually be beneficial to some because you don't need additional application logic, but it also prevents you from adjusting the routing logic if necessary.

Configuring pgpool also proved quite difficult due to the sheer number of configuration options. Perhaps the final nail in the coffin was the feedback we got on pgpool from those having used it in the past. The feedback we received regarding pgpool was usually negative, though not very detailed in most cases.

While most of the complaints appeared to be related to earlier versions of pgpool it still made us doubt if using it was the right choice.

The feedback combined with the issues described above ultimately led to us deciding against using pgpool and using pgbouncer instead. We performed a similar set of tests with pgbouncer and were very satisfied with it. It's fairly easy to configure (and doesn't have that much that needs configuring in the first place), relatively easy to ship, focuses only on connection pooling (and does it really well), and had very little (if any) noticeable overhead. Perhaps my only complaint would be that the pgbouncer website can be a little bit hard to navigate.

Using pgbouncer we were able to drop the number of active PostgreSQL connections from a few hundred to only 10-20 by using transaction pooling. We opted for using transaction pooling since Rails database connections are persistent.

In such a setup, using session pooling would prevent us from being able to reduce the number of PostgreSQL connections, thus brining few (if any) benefits. By using transaction pooling we were able to drop PostgreSQL's max_connections setting from 3000 (the reason for this particular value was never really clear)

to 300. pgbouncer is configured in such a way that even at peak capacity we will only need 200 connections; giving us some room for additional connections such as psql consoles and maintenance tasks.

A side effect of using transaction pooling is that you cannot use prepared statements, as the PREPARE and EXECUTE commands may end up running in different connections; producing errors as a result. Fortunately we did not measure any increase in response timings when disabling prepared statements, but we did measure a reduction of roughly 20 GB in memory usage on our database servers.

To ensure both web requests and background jobs have connections available we set up two separate pools: one pool of 150 connections for background processing, and a pool of 50 connections for web requests. For web requests we rarely need more than 20 connections, but for background processing we can easily spike to a 100 connections simply due to the large number of background processes running on GitLab.com.

Today we ship pgbouncer as part of GitLab EE's High Availability package. For more information you can refer to ["Omnibus GitLab PostgreSQL High Availability."]ha-docs

Database load balancing for GitLab

With pgpool and its load balancing feature out of the picture we needed something else to spread load across multiple hot-standby servers.

For (but not limited to) Rails applications there is a library called [Makara]makara which implements load balancing logic and includes a default implementation for ActiveRecord. Makara however has some problems that were a deal-breaker for us. For example, its support for sticky connections is very limited: when you perform a write the connection will stick to the primary using a cookie, with a fixed TTL. This means that if replication lag is greater than the TTL you may still end up running a query on a host that doesn't have the data you need.

Makara also requires you to configure quite a lot, such as all the database hosts and their roles, with no service discovery mechanism (our current solution does not yet support this either, though it's planned for the near future). Makara also [does not appear to be thread-safe]makara-thread-safe, which is problematic since Sidekiq (the background processing system we use) is multi-threaded. Finally, we wanted to have control over the load balancing logic as much as possible.

Besides Makara there's also [Octopus]octopus which has some load balancing mechanisms built in. Octopus however is geared towards database sharding and not just balancing of read-only queries. As a result we did not consider using

Octopus.

Ultimately this led to us building our own solution directly into GitLab EE.

The merge request adding the initial implementation can be found [here]lb-mr, though some changes, improvements, and fixes were applied later on.

Our solution essentially works by replacing ActiveRecord::Base.connection with a proxy object that handles routing of queries. This ensures we can load balance as many queries as possible, even queries that don't originate directly from our own code. This proxy object in turn determines what host a query is sent to based on the methods called, removing the need for parsing SQL queries.

Sticky connections

Sticky connections are supported by storing a pointer to the current PostgreSQL

WAL position the moment a write is performed. This pointer is then stored in

Redis for a short duration at the end of a request. Each user is given their own key so that the actions of one user won't lead to all other users being affected. In the next request we get the pointer and compare this with all the secondaries. If all secondaries have a WAL pointer that exceeds our pointer we know they are in sync and we can safely use a secondary for our read-only queries. If one or more secondaries are not yet in sync we will continue using the primary until they are in sync. If no write is performed for 30 seconds and all the secondaries are still not in sync we'll revert to using the secondaries in order to prevent somebody from ending up running queries on the primary forever.

Checking if a secondary has caught up is quite simple and is implemented in Gitlab::Database::LoadBalancing::Host#caught_up? as follows:

def caught_up?(location)

string = connection.quote(location)

query = "SELECT NOT pg_is_in_recovery() OR " \

"pg_xlog_location_diff(pg_last_xlog_replay_location(), #{string}) >= 0 AS result"

row = connection.select_all(query).first

row && row['result'] == 't'

ensure

release_connection

end

Most of the code here is standard Rails code to run raw queries and grab the results. The most interesting part is the query itself, which is as follows:

SELECT NOT pg_is_in_recovery()

OR pg_xlog_location_diff(pg_last_xlog_replay_location(), WAL-POINTER) >= 0

AS result"

Here WAL-POINTER is the WAL pointer as returned by the PostgreSQL function pg_current_xlog_insert_location(), which is executed on the primary. In the above code snippet the pointer is passed as an argument, which is then quoted/escaped and passed to the query.

Using the function pg_last_xlog_replay_location() we can get the WAL pointer of a secondary, which we can then compare to our primary pointer using pg_xlog_location_diff(). If the result is greater than 0 we know the secondary is in sync.

The check NOT pg_is_in_recovery() is added to ensure the query won't fail when a secondary that we're checking was just promoted to a primary and our

GitLab process is not yet aware of this. In such a case we simply return true since the primary is always in sync with itself.

Background processing

Our background processing code always uses the primary since most of the work performed in the background consists of writes. Furthermore we can't reliably use a hot-standby as we have no way of knowing whether a job should use the primary or not as many jobs are not directly tied into a user.

Connection errors

To deal with connection errors our load balancer will not use a secondary if it is deemed to be offline, plus connection errors on any host (including the primary) will result in the load balancer retrying the operation a few times.

This ensures that we don't immediately display an error page in the event of a hiccup or a database failover. While we also deal with [hot standby conflicts]hot-standby-conflicts on the load balancer level we ended up enabling hot_standby_feedback on our secondaries as doing so solved all hot-standby conflicts without having any negative impact on table bloat.

The procedure we use is quite simple: for a secondary we'll retry a few times with no delay in between. For a primary we'll retry the operation a few times using an exponential backoff.

For more information you can refer to the source code in GitLab EE:

https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab-ee/tree/master/ee/lib/gitlab/database/load_balancing.rb

https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab-ee/tree/master/ee/lib/gitlab/database/load_balancing

Database load balancing was first introduced in GitLab 9.0 and only supports

PostgreSQL. More information can be found in the [9.0 release post]9-0-release and the documentation.

Crunchy Data

In parallel to working on implementing connection pooling and load balancing we were working with [Crunchy Data]crunchy. Until very recently I was the only [database specialist]database-specialist which meant I had a lot of work on my plate. Furthermore my knowledge of PostgreSQL internals and its wide range of settings is limited (or at least was at the time), meaning there's only so much

I could do. Because of this we hired Crunchy to help us out with identifying problems, investigating slow queries, proposing schema optimisations, optimising

PostgreSQL settings, and much more.

For the duration of this cooperation most work was performed in confidential issues so we could share private data such as log files. With the cooperation coming to an end we have removed sensitive information from some of these issues and opened them up to the public. The primary issue was [gitlab-com/infrastructure#1448]issue-1448, which in turn led to many separate issues being created and resolved.

The benefit of this cooperation was immense as it helped us identify and solve many problems, something that would have taken me months to identify and solve if I had to do this all by myself.

Fortunately we recently managed to hire our [second database specialist]gstark and we hope to grow the team more in the coming months.

Combining connection pooling and database load balancing

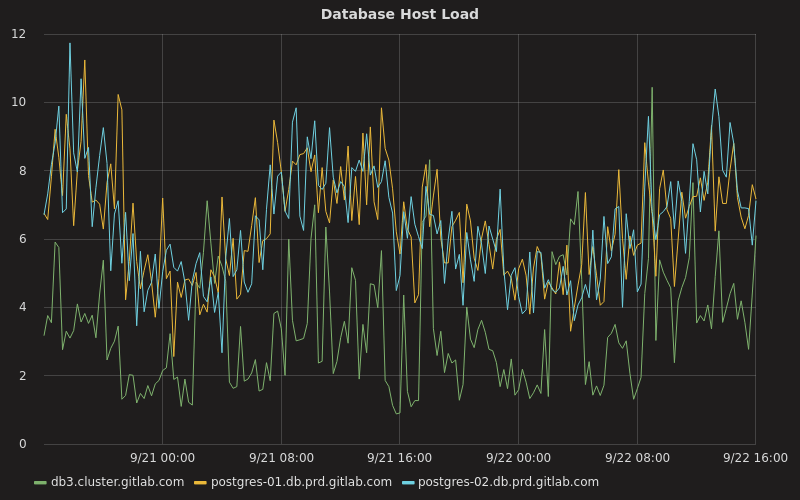

Combining connection pooling and database load balancing allowed us to drastically reduce the number of resources necessary to run our database cluster as well as spread load across our hot-standby servers. For example, instead of our primary having a near constant CPU utilisation of 70 percent today it usually hovers between 10 percent and 20 percent, while our two hot-standby servers hover around 20 percent most of the time:

Here db3.cluster.gitlab.com is our primary while the other two hosts are our secondaries.

Other load-related factors such as load averages, disk usage, and memory usage were also drastically improved. For example, instead of the primary having a load average of around 20 it barely goes above an average of 10:

During the busiest hours our secondaries serve around 12 000 transactions per second (roughly 740 000 per minute), while the primary serves around 6 000 transactions per second (roughly 340 000 per minute):

Unfortunately we don't have any data on the transaction rates prior to deploying pgbouncer and our database load balancer.

An up-to-date overview of our PostgreSQL statistics can be found at our [public

Grafana dashboard]postgres-stats.

Some of the settings we have set for pgbouncer are as follows:

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| default_pool_size | 100 |

| reserve_pool_size | 5 |

| reserve_pool_timeout | 3 |

| max_client_conn | 2048 |

| pool_mode | transaction |

| server_idle_timeout | 30 |

With that all said there is still some work left to be done such as:

implementing service discovery ([#2042]issue-2042), improving how we check if a secondary is available ([#2866]issue-2866), and ignoring secondaries that are too far behind the primary ([#2197]issue-2197).

It's worth mentioning that we currently do not have any plans of turning our load balancing solution into a standalone library that you can use outside of

GitLab, instead our focus is on providing a solid load balancing solution for

GitLab EE.

If this has gotten you interested and you enjoy working with databases, improving application performance, and adding database-related features to

GitLab (such as [service discovery]issue-2042) you should definitely check out the [job opening]job-opening and the [database specialist handbook entry]database-specialist for more information.

- Max Connections

- PgBouncer

- Pgpool

- Hot Standby

- Pgpool Comment Data

- HA Docs

- Makara

- Makara Thread Safety Issue

- Load Balancing MR

- Issue #2042

- Issue #2866

- Issue #2197

- GitLab 9.0 Release

- Load Balancing Docs

- Postgres Stats Dashboard

- Hot Standby Conflicts

- Citus

- Octopus

- Crunchy Data

- Database Specialist Handbook

- Database Engineer Job Opening

- Issue #1448

- Gstark

We want to hear from you

Enjoyed reading this blog post or have questions or feedback? Share your thoughts by creating a new topic in the GitLab community forum.

Share your feedback