Published on: January 24, 2020

11 min read

Upgrading bootstrap-vue in gitlab-ui

How we upgraded BootstrapVue to v2 stable in GitLab UI, our UI library, and what challenges we encountered in the process

{::options parse_block_html="true" /}

Three months ago, we started a process to upgrade bootstrap-vue in gitlab-ui from 2.0.0-rc.27 to the

latest stable version. You may wonder: Why has it taken so long? We found several impediments along the

way caused by backward compatibility issues widespread across GitLab’s codebase. In this blog post

we’ll cover the following topics:

1. How GitLab CI helped us during the migration

When dealing with a situation like this, where one of your libraries introduces a lot of breaking changes that need to be iteratively fixed in the products that depend on them, having access to great tools like GitLab CI can be a huge time-saver, especially in a distributed company like GitLab.

It goes without saying that GitLab itself is heavily tested, with tens or even hundreds of CI jobs

run against every commit. While this is extremely useful, GitLab depends on an official

release of GitLab UI which is pinned in its package.json. This isn't helpful in our case

because we don't want to release a new version of GitLab UI with BootstrapVue 2.0.0 stable unless we're

absolutely certain that it won’t cause adverse effects in GitLab.

While there are several ways to test an unreleased version of an NPM package in a project, we would like to briefly explain how we did it thanks to a few GitLab CI jobs that demonstrate how you can take advantage of this powerful feature for things that go beyond running test suites in your projects.

npm publish

Let's talk briefly about the npm publish command: it is the

command that you would run to publish an NPM package to NPM's registry. When running the command, a

tarball of your package is created and uploaded to the registry where it is tagged with the version

that's defined in your package.json. This is great, but once you run the publish command, a new

version of your package becomes publicly available. Of course you could release beta versions of your

package but then again, you would most likely bloat the registry with versions of your package that

you know won't work. So, is there a way to publish a test npm package outside the npm registry?

yarn pack

What now? Another CLI command? Okay so what does this one do? According to the doc,

yarn pack

Creates a compressed gzip archive of package dependencies.

So this means that it archives your package, like npm publish does, except that the archive will

stay on your computer and won't be uploaded or published to any registry. And you can even give your

archive a name using the --filename flag.

Okay, so how does that help us?

All right, let's see how this is useful in GitLab UI's CI setup. If you look at the .gitlab-ci.yml

file in GitLab UI, you'll see an upload_artifacts

job.

upload_artifacts:

extends: .node

stage: deploy

variables:

TAR_ARCHIVE_NAME: gitlab-ui.$CI_COMMIT_REF_SLUG.tgz

needs:

- build

script:

- yarn pack --filename $TAR_ARCHIVE_NAME

- DEPENDENCY_URL="$CI_PROJECT_URL/-/jobs/$CI_JOB_ID/artifacts/raw/$TAR_ARCHIVE_NAME"

- echo "The package.json dependency URL is $DEPENDENCY_URL"

- echo $DEPENDENCY_URL > .dependency_url

artifacts:

when: always

paths:

- $TAR_ARCHIVE_NAME

- .dependency_url

only:

- /.+/@gitlab-org/gitlab-ui

Notice how this job depends on the build job via the needs option, this means that it will

only run after build has completed, and it will have access to build's artifacts, which, among

other things, contain the production-ready compiled version of GitLab UI. Now upload_artifacts

does 3 important things:

- It declares a

TAR_ARCHIVE_NAMEenvrionment variable which is a combination ofgitlab-uiand the current branch's name, followed by the.tgzextension. - It calls

yarn pack --filename $TAR_ARCHIVE_NAMEwhich, as we've seen above, will create an archive of the package's dependencies, including the production-ready bundle from thebuildjob. - And finally, it lists

$TAR_ARCHIVE_NAMEas one the job's artifacts paths.

The last point is where all the magic happens, because the package's archive now becomes a

downloadable artifact, which means that we have a kind of simple and private registry for all of our

development branches from which we can install GitLab UI's development builds to test them out in

GitLab. Notice how the job also prints a URL which is constructed this way:

$CI_PROJECT_URL/-/jobs/$CI_JOB_ID/artifacts/raw/$TAR_ARCHIVE_NAME. This gives us a direct download

link to the archived package that we can use to install the build in GitLab:

yarn add @gitlab/ui@$DEPENDENCY_URL

Where $DEPENDENCY_URL is the artifact's URL.

This has helped us a lot during this big migration because we were able to open a merge request in

GitLab where the package.json would point to our GitLab UI development build. This allowed us to

benefit from the huge CI pipeline could benefit from the huge CI pipeline in GitLab to run every test

suite, thus giving us a nice overview of what needed to be fixed. It was also very useful in terms of

collaboration, because we were able to involve more engineers in the migration process without

requiring them to setup their local environment in any particular way. They would simply checkout the

development branch, run yarn install, and they would be good to go.

This is only one of the endless possibilities that GitLab CI offers. Hopefully it gave you some ideas for your own special CI job!

2. Bootstrap-vue breaking changes

Different import statements

Importing bootstrap-vue components requires a different syntax. In bootstrap-vue 2.0.0-rc.27 (previous version in production), we imported components directly from the source path:

import BDropdown from 'bootstrap-vue/src/components/dropdown/dropdown';

In bootstrap-vue 2.0, the component source file does not have a default export statement anymore. To circumvent this issue, we changed all import statements to reference bootstrap-vue main import file.

import { BDropdown } from 'bootstrap-vue';

A new slot syntax for BVTable and BVTab components

Tables

Bootstrap-vue BTable dynamically generates Vue template slots based on the table’s column definitions to customize the presentation of content. In bootstrap-vue 2.0, the naming syntax for these slots changed:

<template #cell(project)="data">

GitLab uses BTable widely, and we found several approaches to declare these slots across the codebase:

<!-- Version 1 -->

<template #HEAD_changeInPercent="{ label }">

<!-- Version 2 -->

<template #name="items">

<!-- Version 3 -->

<template slot="project" slot-scope="data">

GitLab test suite detected the components broken by this change when running the tests using the artifact generated by gitlab-ui. We fixed these failures in the upgrade bootstrap-vue merge request.

Tabs

The BTabs component does not have the tabs slot anymore (BV deprecated this slot in previous versions). You should use tabs-end instead.

<template #tabs> <!-- Deprecated version -->

<template #tabs-end> <!-- Use tabs-end instead -->

<li class="nav-item align-self-center">

Contentless tab

</li>

</template>

Heavily refactored tooltip and popover components

The changes introduced in the tooltip component generated the most significant number of side-effects in gitlab-ui and GitLab. From the bootstrap-vue changelog entry for 2.0.0:

Tooltips and popovers have been completely re-written for better reactivity and stability. The directive versions are now reactive to trigger element title attribute changes and configuration changes.

Since the API for these components didn’t change, our codebase shouldn’t have been affected by their refactoring. That wasn’t the case. When we ran the GitLab test suite, all test specs for components that have the tooltip as a dependency failed. As you may realize, those are many Karma, Jest, and unit tests. You’ll wonder... what happened?

Problem 1: The tooltip directive expects to be attached to the DOM document

One of the behaviors introduced by the tooltip component refactoring is that we can’t initialize the component unless it is attached to the document object. If that condition is not satisfied, bootstrap-vue logs the following warning message, and won’t initialize the component:

[BootstrapVue warn]: tooltip unable to find target element in document"

None of our unit tests attach the component under test to the document object. This action could cause memory leaks in Karma unit tests because test suite environments are not isolated.

How did we solve this problem?

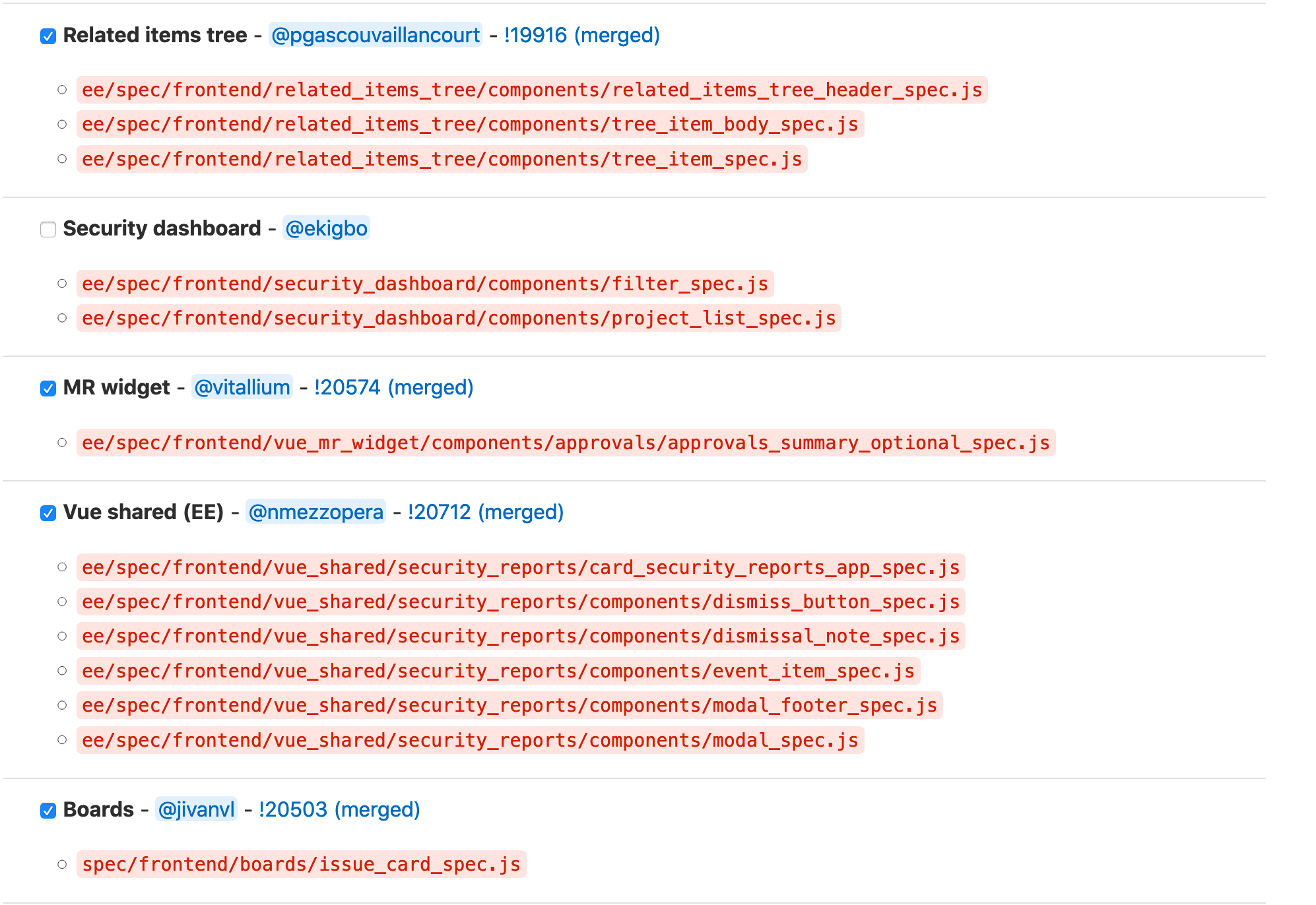

First, we migrated all the failing Karma tests to Jest in separate merge requests (see group 1 and group 2).

We also rewrote those tests to use vue-test-utils instead of a legacy vue test utility we wrote.

This step was essential because Karma doesn’t have dependency mocking capabilities.

Also, when mounting the component under test using vue-test-utils, we can easily attach it to the document using the attachToDocument flag.

The next steps were a mix of migrating Jest specs to vue-test-utils if needed and setting the attachToDocument flag to true.

The work ahead was staggering: We had to fix 74 test suites before calling a victory. Many of those specs required significant changes. To avoid increasing the size of the upgrade MR, we opened separate

MRs for each spec file. Another advantage of using different MRs is that it enabled us to distribute

the migration effort among several hands.

Over time, this strategy became an uphill battle as more failing specs popped-up. We were pursuing a moving target, so we decided to find an alternative. The reason behind adapting the failing tests to work with the rewritten tooltip is because tests were coupled to the tooltip implementation. Instead of honoring that coupling, we mocked the tooltip dependency to eliminate it. As explained by vue test utils:

In unit tests, we typically want to focus on the component being tested as an isolated unit and avoid indirectly asserting the behavior of its child components.

We used Jest manual mock feature to replace the tooltip directive with a shallow version that only provides essential functionality to avoid breaking tests.

export * from '@gitlab/ui';

export const GlTooltipDirective = {

bind() {},

};

export const GlTooltip = {

render(h) {

return h('div', this.$attrs, this.$slots.default);

},

};

Problem 2: Asserting tooltip directive’s internals

We found many unit tests that contained the following assertion pattern:

expect(wrapper.attributes('data-original-title')).toContain(statusMessage);

The purpose of this assertion is verifying that the content of a tooltip attached to a component

is correct. The tooltip directive expects to find its content in the title attribute of an element.

Why were we verifying the data-original-title attribute then? Before bootstrap-vue 2.0, the tooltip

directive unset the title attribute and set data-original-title with the former’s value. All

the specs that asserted the tooltip’s content were coupled to this internal behavior. Once we

upgraded to a version that didn’t follow this behavior, these specs failed.

The solution to this problem is very similar to problem 1’s. First, mocking the tooltip directive

allowed us to decouple unit tests from BV implementation. Afterward, We just needed to replace all

data-original-title references with the title.

Lessons learned

1. Technical debt impacts significantly our ability to upgrade dependencies

This upgrade was costly because it required fixing hundreds of unit and feature tests. The costs could’ve been much lower if we hadn’t had to migrate as many tests to use jest and vue-test-utils. This is a palpable reason to schedule time in each milestone to migrate specs written with legacy practices to modern ones.

The FE department has organized an effort to migrate legacy specs to use jest and vue-test-utils in this epic. The epic also contains guidelines about how to do it. All contributions are appreciated.

2. Avoid testing component’s dependencies internals

Unit tests should focus as much as possible in the component under test and refrain from making assumptions about how the component’s dependencies work. The other factor that increased costs drastically was finding specs that made assumptions about how the tooltip directive worked under the hood. We should strive to mock component’s dependencies to keep unit tests focused.

The FE department has opened a merge request that proposes using higher-level selectors in unit tests. There are scenarios where an integration test is more suited, though. We are also discussing approaches to have a better distinction between unit and integration tests in the frontend.

Useful resources

We want to hear from you

Enjoyed reading this blog post or have questions or feedback? Share your thoughts by creating a new topic in the GitLab community forum.

Share your feedback