Published on: July 11, 2022

7 min read

How to migrate Atlassian's Bamboo server's CI/CD infrastructure to GitLab CI, part two

A real-world look at how a migrated CI/CD infrastructure will work in GitLab CI.

In part one of our series, I showed you how to migrate from Atlassian’s Bamboo Server to GitLab CI/CD. In this blog post we’re going to take a deep dive into how it works from a user’s perspective.

Get started

You’ve deployed the demo so it’s time to play with it to understand how it works.

Let's imagine that one of the members of our project is John Doe. He is a software engineer responsible for developing some components (app1, app2, and app3) of the entire product, and he and his team would like to test those components in several combinations in myriad preview environments. So, what does that look like?

First of all, let’s make some commits to the app1, app2, and app3 source code and get successful builds upon those commits.

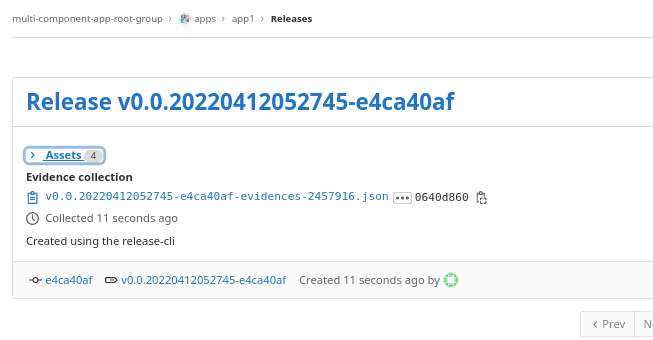

After that, we should create releases for those apps to be able to deploy them (as the deployment part of the apps CI config only shows when being triggered by a Git tag, i.e., a GitLab release). A release can be created by launching the last step (manual-create-release) in a commit pipeline. That would give us a new release with the ugly name containing the date and commit SHA in the patch part (in accord to semver scheme):

On the Tags tab for the same app you now can see a deployment part of the pipeline has been triggered by the just created GitLab release but no actual environments to deploy are displayed (the _ item in the Deploy-nonprod stage is not an env):

Create an environment

But before that we have to briefly switch to another team who is responsible for preparing infrastructure IaC templates. Navigate to the infra/environment-blueprints project and pretend you are a member of that team doing their job. Namely, imagine you have just created some initial set of IaC files (they are already kindly prepared by me and present in the repository). You’ve tested them and now you feel that they are ready to be used by the other members of the project. You indicate such a readiness of a particular version of the IaC files by giving it a GitTag. Let’s put a tag like v1.0.0 onto the HEAD version.

You will see how the tags are going to be used immediately. But first let's make some changes to the IaC files (e.g., add a new resource for some of the apps) and create a second Git tag, let's say v1.1.0. So, at this moment we have two versions of IaC templates (or blueprints) for our infrastructure - v1.0.0 and v1.1.0.

Deploy an app into the environment

Now we can return back to John and his team. We assume John is somehow informed that the version of the IaC templates he should use is v1.0.0. He wants to create a new preview environment out of the IaC templates of that version and put app1 and app2 into that env.

(Here starts a description of how a user interoperates with the infrastructure-set Git repo. Notice that though the eventual idea is that it should be a Merge Request workflow – where you first get a Terraform plan within a Merge Request and can apply such a plan by merging the MR – which is widely advocated by GitLab but for the sake of simplicity here the MR workflow is not implemented and instead direct push commits into a branch are made).

John wants the env to be named preview-for-johns-team. He creates a new branch in the infrastructure-set repo with that name and puts two files into it: a version.txt containing text v1.0.0 and apps.txt with text app1 app2 inside (the files format and its content is utterly simplified).

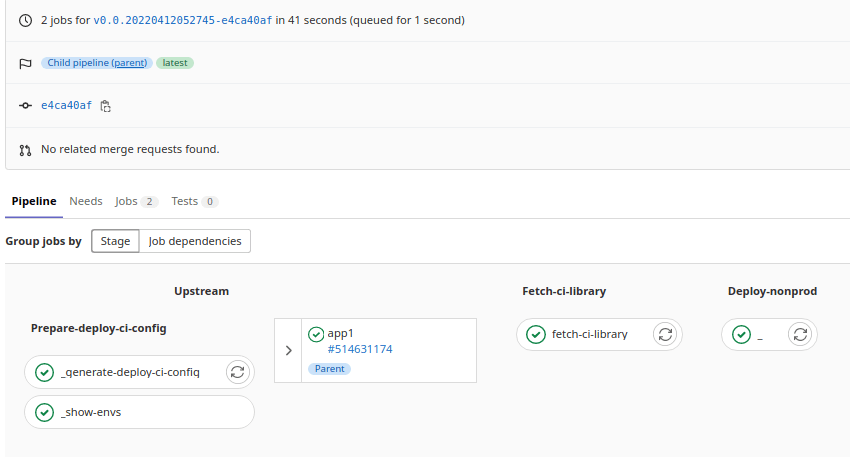

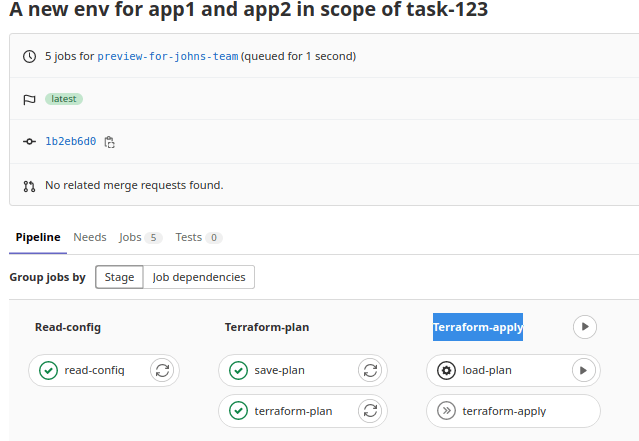

The infrastructure-set pipeline is triggered by the new branch and first generates a Terraform plan using the set of the Terraform files indicated by the tag specified in version.txt. John reviews the plan and wants to proceed with creating the environment by starting the Terraform-apply stage:

(To store the Terraform plan as artifact and Terraform state the embedded features of GitLab are leveraged - Package Registry and Terraform HTTP back-end by GitLab.)

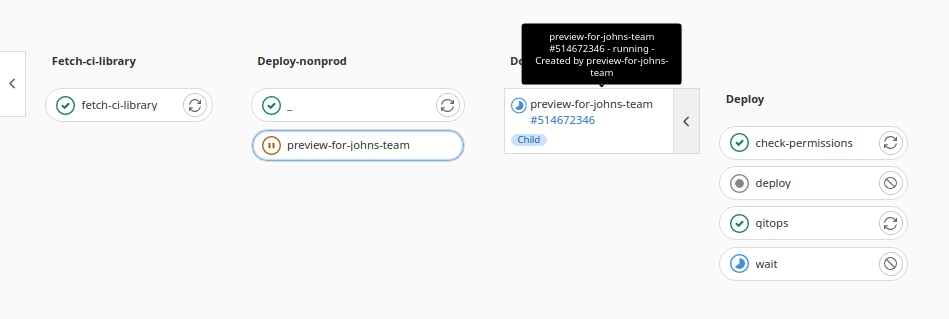

Now return to the app1 project and rerun the pipeline for the app1 release we created previously to make it regenerate a list of environments to deploy. You should see that the preview-for-johns-team item has appeared in the list of the environments:

Click the arrow button to deploy. Then refer to the Deployments/Environments section of the app1 project to ensure a new env with the app1 release deployed into it is displayed.

We have successfully created a new environment and deployed one of the apps into it!

Notice that although the above describes how users manually deploy the applications into an environment after it has been created which doesn’t look really convenient, in a real life scenario we most likely would have some additional step in the infrastructure-set pipeline that runs after Terraform successfully finishes creating an environment and triggers deployment pipelines for all the applications specified in the apps.txt. In that situation, we would need to establish which versions of the applications should be deployed in such an automated manner - for example, those might be the latest versions available for each app or the versions currently deployed to production, etc.

Update an environment's infrastructure

John got notified that a new version of the infrastructure templates is available (you remember that v1.1.0 tag in the environment-blueprints repo?). His team wants to assess how app1 would work within the new conditions. They decide to update an existing env, namely preview-for-johns-team, for that purpose.

John walks to the preview-for-johns-team branch of the environment-set repo and changes version.txt's content from v1.0.0 to v1.1.0. The branch pipeline gets triggered and first shows John a Terraform plan for a diff comparing the current state of the environment. After reviewing and accepting that diff, John proceeds with actual updating the environment by launching Terraform-apply stage. That's it!

Advantages and disadvantages

Virtues

Given that this case assumes migrating from some existing CI/CD infrastructure based on Atlassian Bamboo with a lot of users who are familiar with it, the proposed solution leverages the native capabilities of GitLab so that it mostly keeps the concepts and workflows used with Bamboo. This strategy makes the process of migration more smooth for the users.

The solution sticks to the GitOps tenets and empowers a project with all the virtues provided by Git. For example, it's usually easy to track any changes in the infrastructure back to Git repos. (It may not be so easy for the environment-set project where we do not have the infrastructure changes captured in Git commits, but in that case a task of finding differences between two states of a particular environment can be accomplished by fetching the two versions of the environment-blueprints repo corresponding to those states denoted in the version.txt and figuring out the differences by using any apt tool.)

The solution tends to support user self-service where most of the tasks of changing the infrastructure can be performed only by those familiar with the basics of Git and Terraform. As a result, it offloads the DevOps team from some part of the work and removes dependence on the Ops department which comes in really handy, especially for large-scale projects.

Shortcomings

Besides the mentioned deficits which stem from the necessity to utterly simplify all the aspects of this demo to make it comprehensible and possible to prepare in a sensible amount of time, this solution possesses some shortcomings that have to be resolved by using external tools to make this solution appropriate for a real life usage.

For example, there is no way to have a central dashboard with an aggregated view of all the environments with all the apps and their versions deployed into the envs. This would require creating some custom SPA web app which would gather information from GitLab via API.

We want to hear from you

Enjoyed reading this blog post or have questions or feedback? Share your thoughts by creating a new topic in the GitLab community forum.

Share your feedback