"Transparency is only a value if you do it when it is hard" 👁

That's one of the lines that has stuck with me from my GitLab Inc. onboarding nearly 2 years ago. You know where practicing transparency is typically "hard"?

Security.

Thankfully, I can honestly say that I work on a Security team that not only pushes the transparency boundaries in the industry, but also within GitLab itself. Take our RedTeam, they’ve put out a whole public project called Tech Notes which contains deep dives on some of the challenges and vulnerabilities they’ve encountered in their work. They also just held their first-ever, live and public AMA/Ask Me Anything on January 26, 2021 and responded to over a dozen questions about the work that they do and how they go about doing it here at GitLab. If you joined us, thank you! If you missed it, check out the replay below. We’d love to hear from you on whether you’d like to see an event like this in the future with our Red Team (or another group within Security) -- just drop a comment below, tweet/DM one of us on twitter or message GitLab Red Team email.

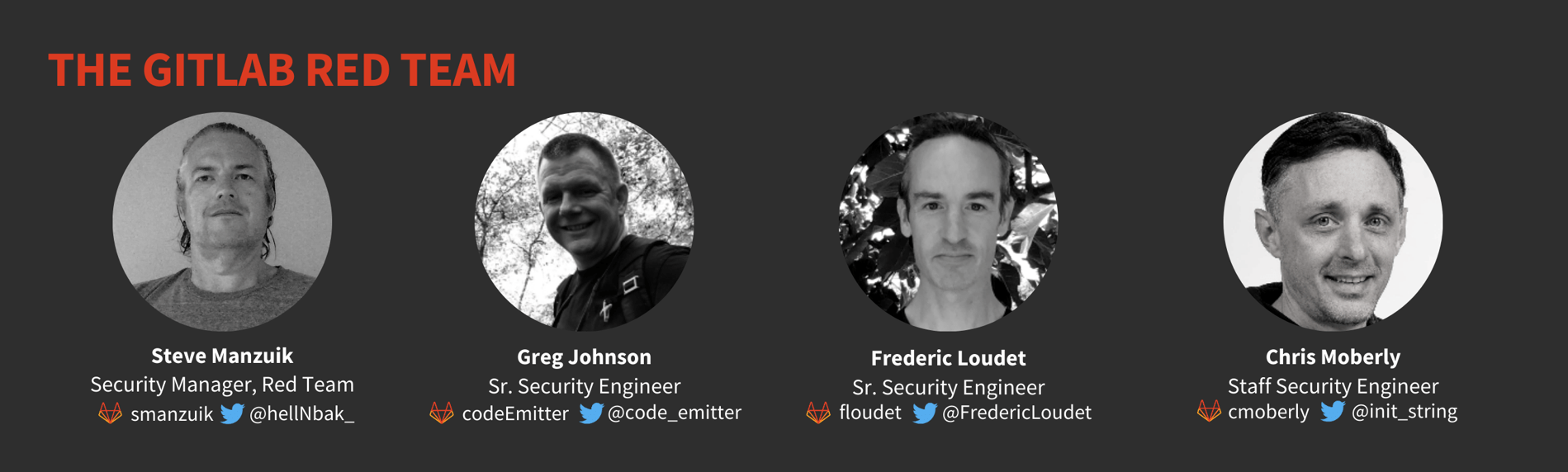

Who’s on the team

Here’s what you asked

Considering you're a full remote company, persistence on endpoints is still relevant in your activity or hunting tokens or credentials make more sense? Some Cloud services do not require you to reach them with VPN, so SSO tokens or credentials can be enough in some cases to reach sensitive information.

Note: Added for clarity: “endpoint” refers to laptops and mobile devices.

Steve Manzuik: I think the security of our endpoints is still very important but you are right about SSO tokens / auth cookies being a bit higher priority for us. This is why Greg spent some time creating tooling, gitrob and token hunter, around finding secrets that get accidentally leaked in code. In addition, many of the other scenarios we have tested have been focused on obtaining auth tokens or credentials.

Greg Johnson: You’re definitely making a good point about initial access here. Early on, there weren’t very many options for tooling in terms of hunting for the types of tokens you mentioned. We’ve put a lot of time and iterations into improving our ability to find sensitive leaks quickly. The tools that Steve mentioned are constantly being honed, changed, and reimagined completely to improve our techniques and the accuracy of the tools.

Chris Moberly: I have a bit of a non-technical, non-operation take on this as well. We’re an internal Red Team, meaning that our “targets” are often our colleagues and friends. These are people that we work with every day. Just in terms of efficiency, it is important to gain and maintain trust with them. For example, if we have a question about how a tricky bit of code works, we can just pop into an internal development Slack room and ask. We do this all the time, and our colleagues have been amazing at trusting our positive intentions and helping us out. But, even beyond efficiency, it simply would make for an unpleasant work environment if our colleagues were constantly worried about us trying to exploit their laptops. This is especially true in an all-remote company where those laptops are inside their homes and often double up as personal machines. Because of this, I really prefer emulating endpoint exploitation and persistence; either with a dummy device or a willing target who is 100% aware of what is going on. This is where the concept of an “assumed breach” can also come into play. We need to understand the threat model for an endpoint compromise, demonstrate the extraction of credentials, cookies, etc that would exist there, and then move on to attacking the cloud services as others have mentioned above. I think a bit of persistence emulation would be good for testing the efficacy of endpoint management tools: like, can we keep an implant running on a standard endpoint build for the duration of an operation without triggering alerts? If so, what can be fixed to get those alerts happening sooner?

To evaluate an insider threat, do you consider to run exercises from authorized users? I mean, run an exercise to simulate a legit change in your system but with some malicious effects? For eg. spin-up a new web service or whatever with some backdoors in order to be able to keep access?

Steve Manzuik: Yes, we also run exercises that we call “assumed compromise scenarios” which fall in line with this exact question. The high-level premise is focused on what happens once an attacker gains access: legitimate or otherwise. Then we look at what that attacker may do, where they may pivot, and what actions we can detect and alert on.

Frederic Loudet: As an example, we will start an operation from a shell inside our infrastructure (on a VM or a container), assuming a rogue internal user is starting from there or someone managed to compromise some of our defenses and get this shell access.

Greg Johnson: We also model many of the ways an attacker may try to achieve persistence with these operations.

When conducting adversarial simulation and/or exploratory penetration testing operations, what systems / platforms do you use to store, collaborate on, and manage testing related intelligence (execution times, commands, findings, etc.)?

Steve Manzuik: We leverage our own product, GitLab, as well as a product known as Vectr that helps us map our attacks and related detection/response.

Chris Moberly: We also leverage our own self-managed GitLab instance to make TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) automated and repeatable. This is done by hosting our custom attack tooling in projects and writing CI jobs that run them on demand and/or at scheduled intervals. We have one tool that builds and executes in CI and outputs the results onto a GitLab Pages site that requires multi-factor authorization to access; which is a pretty cool usage of our available tools. Just to echo Steve’s mention of Vectr - that tool is awesome, I highly recommend checking it out. And if you want to brainstorm creative ways to use GitLab for tracking the operational bits, you can type “GitLab for project management” into your favorite search engine to find some cool blogs and videos on the topic.

How do you promote collaborations between your team and other security / application groups within your organization? What sort of collaborative operations does your team work on?

Steve Manzuik: This is an area where our Red Team is a bit different than a traditional one. We try to be as transparent and open about our operations as possible. There are of course always going to be cases where we need to be stealthy and share less but we attempt to limit those as much as possible. Typically, when we are performing an operation we will pull in a resource from impacted teams to at least be aware of what we are doing. So for example, we recently worked on an operation focusing on our development processes and had resources from our AppSec team working directly with us and helping us with ideas and knowledge. Same goes when we are touching infrastructure things -- we will involve someone from the infrastructure team.

Fred Loudet: As another collaboration example, on some operations, we will create a dedicated chat channel and invite team members (infrastructure or others depending on the operation) so they can follow the operation “live” as we try to comment on what we do/what we find. It works really well, we even get ideas from those other members. They see we are not hiding anything from them and not doing it to make them look bad (ok, we may refrain from saying “yoohoo” if we manage to gain something good!).

How do you break the stigma of ‘red teamers are here to attack us’ within your organization? How do you promote an environment of trust when certain teams may go into collaborations/operations with the mindset of ‘these people are going to tell me my baby is ugly’?

Steve Manzuik: This is why we try to be as transparent as possible when we are planning our operations. Before we even start work, we document the general test plan and goals and then typically meet with stakeholders to ensure that they are on the same page. It also helps that our Red Team is experienced enough to be able to deliver bad news without attaching ego or judgement to it as well. We make sure that everyone knows that we are here to help vs. just here to judge their technical work.

Fred Loudet: As Steve says, we are lucky Gitlab is pushing “transparency”, so it makes everyone more open to reviews and remarks from various teams. As mentioned in question 4, when it makes sense, we really try to involve the “targeted” teams fully into the operation, including if possible within the execution phase. And so far it works well, everyone sees what could be seen as “bad news” as “opportunities to improve” (It also helps Gitlab promote the “right to make mistakes and learn from them”).

Greg Johnson: There is a very human aspect to red teaming you can’t ignore. Building trust with people is in essence a very simple formula. We try to make sure that the people we interact with expect a positive experience through the planning and preparation steps that Steve and Fred mentioned, first and foremost. We also do our best to make sure that this expectation of a positive experience is met in the end through all phases of the operation including remediation so there are as few gaps as possible between the positive experience people expect and what they actually get.

When planning an adversarial simulation operation, do you try to mimic the TTP usage patterns of known actors or do you tailor TTP usage to your organization?

Steve Manzuik: Both. We leverage MITRE’s ATT&CK framework where we can, but have also had to adjust to some more cloud specific TTPs that are not well documented in ATT&CK. From our perspective, both leveraging the known TTPs as well as being crafty and coming up with our own are both very important to help raise the security bar.

Greg Johnson: In the end, we don’t limit our creativity, but we do make an effort to try to mimic attacks that leverage known vectors as often as we can. We draw from a lot of different sources to inspire our operations as legitimate attackers will do the same.

Chris Moberly: To add to Steve’s point, ATT&CK is organized by Tactics, which are high level things like “Initial Access” or “Persistence” and then Techniques, which are very specific things like “create a systemd service” or “abuse set-uid binary”. The Tactics are a really solid foundation for pretty much everything we do, and we try to use those wherever we can. For the Techniques, though, MITRE prefers to include only items that have been discovered in the wild and have some level of attribution. That makes sense for the framework, but at GitLab we’re working with an environment that is quite modern (no physical networks, no Active Directory, etc). We need to be a bit ahead of the curve in terms of developing our own techniques: because we know they will work, and we want to be able to detect and respond to them now. So, we put in some serious time researching possible post-exploitation techniques for the various environments we use. We try to write about those things publicly in our Tech Notes, as well, so that others can use them. Personally, I find this one of the more “fun” parts of the job.

I think we’ll probably also take a look at replaying known-attacks that hit major news headlines. One of the primary goals of security is to basically stay out of the news, so we can look at things like the recent drama with SolarWinds and say “how did it happen to them, could it happen to us, and what would happen if it did?”. That type of operation would look much more closely emulating the known tactics of known actors.

Follow up question: Are any of those cloud TTPs that aren't tracked in MITRE ATT&CK published outside of vectr or where the public can access them?

Steve Manzuik: This is something that we need to take a look at and if/when we do, we’d be publishing them in our Tech Notes.

Chris Moberly: Some of these are already published there, in a blog-like format, but we could certainly produce more ATT&CK-like formatting if there is an appetite for it. If so, let us know! mailto:

What exceptional/unusual skills do you have in your Red Team and how diverse is the skillset across the team?

Steve Manzuik: I don’t know if we have any “unusual skillsets” that relate directly to our work. But our team has a variety of experiences and skills across all the security domains. Something that I know I look for when we are bringing in new team members is the ability to learn quickly. The fun but also hard part of our job is that things are always changing and there is always something new for us to quickly learn.

Greg Johnson: I will say that our skill sets seem to compliment each other very well. We each have areas of strengths and weaknesses. Usually if I have a knowledge gap I can fill it on the immediate team I work with.

Fred Loudet: There are however some “traditional” skillsets that are not useful at all here 😄! Anything Active Directory/Microsoft related is “useless”, same for “physical office” related skills like wireless or breaking into buildings. Our core skills basically revolve around coding/web/cloud computing.

Chris Moberly: I would say I’m probably the best on the team at writing low-quality code lacking in any tests. :)

Fred Loudet: I am pretty certain I write crappier code!

Greg Johnson: We’ll see about that!

Note: in our Jan 26 live AMA we ran out of time before being able to answer all the great questions we received. We’ll answer them below!

Does any of your testing focus on product security? (e.g. Testing if using GitLab would make a good c2 channel)?

Steve Manzuik: Yes, in a lot of cases our exercises will either use functionality of our product or will be directly against the product. That said, we do stay away from doing appsec type testing which would overlap with what both our Bug Bounty and AppSec team focus on.

Chris Moberly: Ha! I love this question as it starts out pretty basic and then drops a really interesting bombshell at the end there. To start with the basic part, of course leveraging new or known bugs in a core product is always useful for a Red Team, so we definitely do that. But, personally, I find that the way a product is customized tends to be what introduces the most risk. So we look at the various dials people can turn, and how that could potentially provide an entry point into a system. Mark Loveless wrote a great blog recently about making sure your self-managed GitLab instance is secure, that one is worth a read Note from Mark: also see this project.

Chris Moberly: On to your next point. To start with, please do not try to use gitlab.com as a covert C2 channel. I'd have to read through the terms to find how many that breaks, but I imagine a few. I will say, GitLab can be self-managed, and there are some amazing things you can do with CI jobs and the "GitLab Runner" agent.

Greg Johnson: GitLab is used in very creative ways to manage all kinds of projects and while we don’t want to discourage creative uses, we also don’t want it to impact other users etc. We look at abuse scenarios as well to help us improve our detection capabilities and defenses.

How do you address conflict in your team? Is it something that’s encouraged and if you have a diverse set of skills then differences in opinion stand to exist correct?

Chris Moberly: I think we often have different ideas on how to approach things, but personally I've never felt that tread into the territory of "conflict". Because we are a small team (1x manager, 3x engineers) that is spread across time zones, we do a lot of work asynchronously. I think this setup actually has some built-in ways to work through differences in opinion. For example, instead of just bouncing ideas back and forth at the beginning of a project, we'll often take the time to come up with an initial proof-of-concept for an idea before sharing. If someone has a different take on it, it might take too long to simply say "I think we should do x instead", as we'd have to cycle through a day or two to get everyone to chime in. So, instead, that person will also come up with a proof-of-concept (PoC) for their idea. At this point, we have several working methods to compare and choose from - or, often we will discover while working on a new PoC that maybe the original idea was best after all.

Fred Loudet: On top of what Chris said, there is also the human factor and I think we are lucky no one in the team is particularly stubborn or has a strong ego 😉! I don’t recall that we’ve had real“conflicts”, just different ideas but so far (crossing fingers!), we’ve managed to discuss in a non conflicting manner and chose what looked like the best solution to all of us. The Gitlab handbook even has a section regarding conflict.

In terms of the make-up of your team, is diversity in gender, background and race something that’s important and a factor in your team when considering the candidates, or do you find yourself picking from the same pool of candidates?

Steve Manzuik: One of the advantages of GitLab being an all remote company is the fact that we can literally hire a candidate from anywhere in the world. Having this huge talent pool to pick from means that we can absolutely focus on diversity for our teams. Today, as you may have noticed from the AMA our team is not all that diverse when it comes to gender and race. However, we do have a diverse set of experiences to bring to the table. We of course want to become much more diverse in all of the other areas and will consider these factors as we grow the team. In addition, it’s worth checking out this blog post, “What it's like to work in Security at GitLab” from Heather Simpson on our security team that highlights other team members across security and our efforts to build a diverse team.

Does Gitlab as a company and overall executive management, understand the value the Red Team brings to the success of the company and how do you communicate the impact/successes of your Red Team activities? In some organisations, the security team is considered a cost to the business and a necessary evil but that’s about it.

Steve Manzuik: In almost an overwhelming way our executives are always very interested in what our Red Team is up to. We find ourselves to be very lucky to have the support from my direct manager, his manager and then our executive team all the way up to our CEO. I think for GitLab it helps that everyone in that chain is technical and understands not only the value that we can bring but also that we can help reduce risk. That doesn’t mean that we have free reign though, we alway make sure that we communicate what we want to do and why we want to do it. Before any exercise begins we have already built a skeleton methodology / approach and defined what it is that we are trying to accomplish and why that matters to the company. When we hit roadblocks or snags we are quick to communicate those as well. GitLab’s value of transparency really helps us out here a lot.

With regards to career growth, how supportive has Gitlab been to the different members on the team and the different career paths they want to take which may be non-traditional?

Chris Moberly: GitLab has a great handbook entry on career growth, it's worth a read. One of the things I really like about GitLab is that the desire to remain technical doesn't result in an early career dead-end. For starters, there are individual-contributor roles beyond "Senior" that allow one to continue progressing without taking on a management position. Next, there is a HUGE focus on taking time for learning and development; I try to spend most Fridays focused on taking online courses, reading books, and doing research that could be leveraged by the team. Beyond that, every other group at GitLab is always extremely helpful when it comes to knowledge sharing. So, I make sure to spend time with our friends on the Blue Team ([SIRT](/handbook/security/#sirt