Published on: July 6, 2022

6 min read

Why we're sticking with Ruby on Rails

GitLab CEO and co-founder Sid Sijbrandij makes the case for Ruby on Rails.

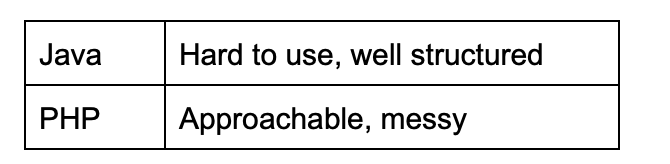

When David Heinemeier Hansson created Ruby on Rails (interview), he was guided by his experience with both PHP and Java. On the one hand, he didn’t like the way the verbosity and rigidness of Java made Java web frameworks complex and difficult to use, but appreciated their structural integrity. On the other hand, he loved the initial approachability of PHP, but was less fond of the quagmires that such projects tended to turn into.

It seems like these are exclusive choices: You either get approachable and messy or well-structured and hard to use, pick your poison. We used to make a very similar, and similarly hard, distinction between server-class operating systems such as Unix, which were stable but hard to use, and client operating systems such as Windows and MacOS that were approachable but crashed a lot.

Everyone accepted this dichotomy as God-given until NeXT put a beautiful, approachable and buttery-smooth GUI on top of a solid Unix base. Nowadays, “server-class” Unix runs not just beautiful GUI desktops, but also most phones and smart watches.

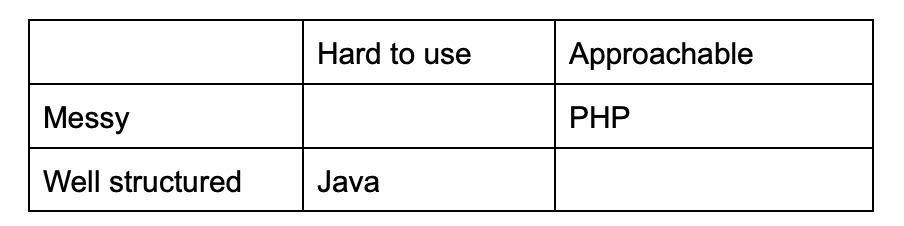

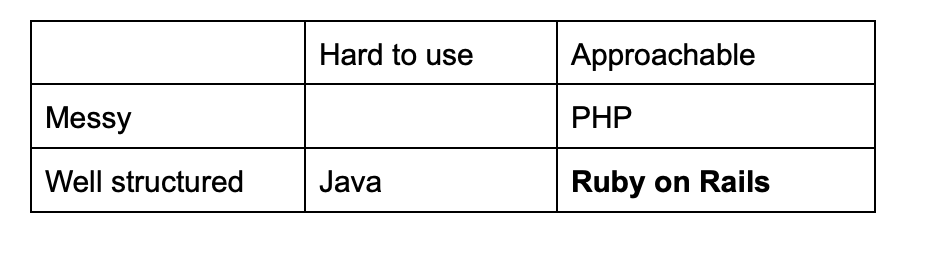

So it turned out that approachability and crashiness were not actually linked except by historical accident, and the same turns out to be true for approachability and messiness in web frameworks: They are independent axes.

And these independent axes opened up a very desirable open spot in the lower right hand corner: an approachable, well-structured web framework. With its solid, metaprogrammable Smalltalk heritage and good Unix integration, Ruby proved to be the perfect vehicle for DHH to fill that desirable bottom right corner of the table with Rails: an extremely approachable, productive and well-structured web framework.

When GitLab co-founder Dmitriy Zaporozhets decided he wanted to work on software for running his (and your) version control server, he also came from a PHP background. But instead of sticking with the familiar, he chose Rails. Dmitry's choice may have been prescient or fortuitous, but it has served GitLab extremely well, in part because David succeeded in achieving his goals for Rails: approachability with good architecture.

Why modular?

In the preceding section, it was assumed as a given that modularity is a desirable property, but as we also saw it is dangerous to just assume things. So why, and in what contexts, is modularity actually desirable?

In his 1971 paper "On the Criteria to be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules", David L. Parnas gave the following (desired) benefits of a modular system:

- Development time should “be shortened because separate groups would work on each module with little need for communication.”

- It should be possible to make “drastic changes or improvements in one module without changing others.”

- It should be possible to study the system one module at a time.

The importance of reducing the need for communication was later highlighted by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man Month, with the additional communication overhead one of the primary reasons for the old saying that "adding people to a late software project makes it later."

We don’t need microservices

Modularity has generally been as elusive as it is highly sought after, with the default architecture of most systems being the Big Ball of Mud. It is therefore understandable that designers took inspiration from arguably the largest software system in existence: the World Wide Web, which is modular by necessity, it cannot function any other way.

Organizing your local software systems using separate processes, microservices that are combined using REST architectural style does help enforce module boundaries, via the operating system, but comes at significant costs. It is a very heavy-handed approach for achieving modularity.

The difficulties and costs of running what is now a gratuitously distributed system are significant, with some of the performance and reliability issues documented in the well-known fallacies of distributed computing. In short, the performance and reliability costs are significant, as function calls that take nanoseconds and never fail are replaced with network ops that are three to six orders of magnitude slower and do fail. Failures become much harder to diagnose if they must be traced across multiple services with very little tooling support. You need a fairly sophisticated DevOps organization to successfully run microservices. This doesn't really make a difference if you run at a scale that requires that sophistication anyhow, but it is very likely that you are not Google.

But even if you think you can manage all that, it is important to note that all this accidental complexity is on top of the original essential complexity of your problem, microservices do nothing to reduce complexity. And even the hoped-for modularity improvements are not in the least guaranteed, typically what happens instead is that you get a distributed ball of mud.

Monorails

By making good architecture approachable and productive, Rails has allowed GitLab to develop a modular monolith. A modular monolith is the exact opposite of a distributed ball of mud: a well-structured, well-architected, highly modular program that runs as a single process and is as boring as possible.

Although structuring GitLab as a monolith has been extremely beneficial for us, we are not dogmatic about that structure. Architecture follows needs, not the other way around. And while Rails is excellent technology for our purposes, it does have a few drawbacks, one of them being performance. Luckily, only a tiny part of most codebases is actually performance critical. We use our own gitaly daemon written in Go to handle actual git operations, and PostgreSQL for non-repository persistence.

Open Core

Last but not least, our modular monolith turns our Open Core business model from being just a nice theory into a practical reality. Although Rails does not accomplish this by itself, that would be our wonderful contributors and engineers, it does lay the proper foundations.

In order to reap the true benefits of open source, the source code that is made available must be approachable for contributors. In order to maintain architectural integrity in the face of contributions from a wide variety of sources, and to keep a clear demarcation line between the open and closed components, the code must be very well structured. Sound familiar?

Wouldn’t it be better to have a proper plugin interface? Or better yet, a services interface modeled on microservices? In a word: no. Not only do these approaches impose deployment and integration hurdles that go far beyond “I made a small change to the source code," they often enforce architectural constraints too rigidly. Anticipating all the future extension points is a fool's errand, one that we luckily did not embark on, and do not have to.

With our boring modular monolith, users and other third-party developers can and do contribute enhancements to the core product, giving us tremendous leverage, coupled with an unbeatable pace and scalability of innovation.