Published on: March 27, 2020

13 min read

Improving iteration and collaboration with user stories

From problem validation to implementation, here's the Release Management team workflow for building user-centered features at GitLab.

Incorporating UX into Agile practices is a known challenge on software projects. One of the most common rants from design teams is how Agile does not embrace UX.

GitLab's focus on results empowers us to create processes that work best for us, our organization, constraints, and opportunities. That includes applying Agile principles to efficiently approach how we design our product.

On GitLab's Release Management team, we rely on User stories to help Product Designers, Product Managers, and Engineers understand how the features we prioritize affect our end users.

By expressing one very specific need that a persona has in the format of a user story, our team has seen the following benefits:

- Keep the scope of feature proposals minimal, while focusing on users instead of solutions.

- Engage in a conversation with our engineering team and stakeholders, so they can help raise technical constraints and more easily estimate implementation effort.

- Provide an essential foundation for the next phases of design.

- Proactively identify follow-up stories to iterate on.

We base our user stories on real data

To ensure we're building GitLab features that are relevant to our target market, as a design practitioner, I partner up with Jackie (Product Manager) and Lorie (UX Researcher) to talk to our users, identify patterns, determine priorities, and translate research into actionable insights.

User stories are just another way to articulate the user insights into the features we prioritize. Problem validation is also key to building strong user stories that will deliver a great user experience.

Remember: great user stories are informed by real user insights! There is no other way to achieve user-centered design.

How a user story was turned into an MVC for Deploy Freezes

When we started talking about the value of being able to restrict deployment time frames and declare accepted windows of code releases in enterprise and regulated industries, our Product Manager turned to customer interviews to validate our assumptions. We surveyed more than 200 participants and interviewed five customers about what we call Deploy Freezes. As a result, we were able to understand the interplay of Deploy Freezes with Release Runbooks, as well as how this problem impacts the GitLab stages of Secure and Plan.

What we learned from problem validation

We learned that for teams that are not global, the ability to halt CI/CD deployments in off hours or suspend CI/CD pipelines on weekends when there is limited team availability can be critical. These users were usually configuring Deploy Freeze policies manually or outside of the GitLab system. Interlocking these policies within CI/CD and automation is a must have to support our users.

Additionally, when looking at dogfooding Deploy Freezes, our internal customers (Production and Delivery teams at GitLab) may need to support users freezing code deploys as they relate to special events like big company announcements, live streamed content, and holidays.

The main difference between this and a pipeline implementer for a .gitlab-ci.yml file is that the authors of these kinds of pipelines are much less technical, and even editing yaml might be a challenge — though they will still need to understand markdown. The personas responsible for enforcing those policies include: Release managers (Rachel), DevOps Engineers (Devon), Software Developers (Sasha), and Development Team Leads (Delaney).

Through research, we identified that our next focus areas should be setting Deploy Freezes in the UI on a project instance level (and eventually on a group level), having a dashboard to report across environments, and logging failed attempts for deployments during a freeze window.

From user insights to user stories

As I start working on the design phase of the MVC, I'll break my tasks into the following steps:

- Work with my Product Manager to identify the main user story.

- Identify possible scenarios and edge cases with the entire team.

- Write acceptance criteria for user stories and create a low-fidelity prototype.

- Discuss and iterate with the team, and move the prototype to high fidelity.

The typical format of a user story is a single sentence: “As a [type of user], I want to [goal], so that [benefit]”. Toward the beginning of the design phase, I documented this user story:

As a DevOps Engineer/Release Manager, I want to specify windows of time when deployments are not allowed for an environment with my GitLab project, so that I can interlock it within CI/CD and automation.

Looking back at the extensive research our Product Manager conducted, as a designer, I am confident that my user story focuses on the right persona and that the scope covers one specific use case (specifying Deploy Freezes on a project level). All other scenarios, such as dashboard, reporting, group level configuration, and auditing are too large for the MVC. This user story also talks about what we are going to build, not how we are going to do it.

It is important to highlight that for some organizations, the DevOps Engineer and Release Manager personas merge into one, where parties responsible for releases also need to keep a hand in development, creating code and contributing to applications, outside of automation. This is one of the reasons why when designing for Release Management, I need to remember our users might have different levels of familiarity and expectations with developer-centered flows.

Thinking big as a team

I carefully consider the development proposal and team conversations to understand the goals and constraints that can inform my initial user story. Every single member of the Release Management team is design minded, so collaborating to improve my design proposals is usually a no brainer!

Instead of collecting user stories in our backlog, we groom and refine them on the fly during the planning phase. Being an all-remote company requires some adjustments to my design process, and our team tries to work as asynchronously as possible.

We tackle collaboration in many different ways: by using issue threads, during Think Big sessions, PM/UX sync calls, 1:1s, and via Slack messages. The most important thing is that every design and technical decision we make is incorporated back into a single source of truth (SSOT) -- in our case, the MVC issue.

Updating the scope and acceptance criteria of issues is a shared responsibility between my Product Manager, the Engineers, and me. We do our best to collect all relevant information, so that our customers and counterparts can have a clear understanding of what we are delivering in the next milestone.

Our team (UX, FE, BE, PM) met to discuss the latest decisions made and discoveries about deploy freezes. Watch on GitLab Unfiltered.

Defining the acceptance criteria

During our refinement process, I learned from engineering that we could specify timeboxes for the freezes using cron syntax, and that we could reuse this from the existing Pipeline schedules capability. Hooray! Engineers also proposed that the gitlab-ci.yml file would instruct the pipeline to not run per the cron syntax. They also thought that it would be great to automatically retry the job and continue the deployment process when the freeze period was over.

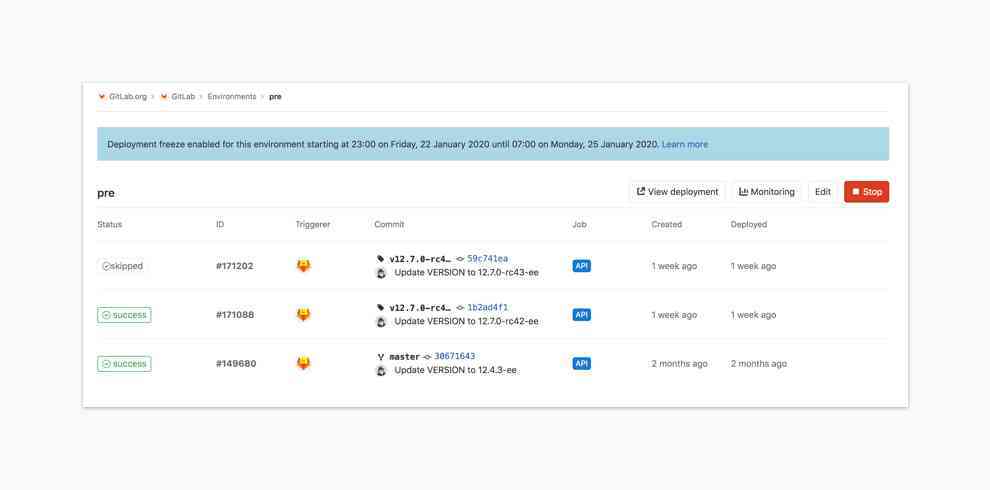

On the design side, my additional proposal focused on notifying users on the interface when a freeze period would be enabled for specific environments. This was especially important to inform users that are consuming the deployments, and not necessarily the people involved in setting up Deploy Freezes.

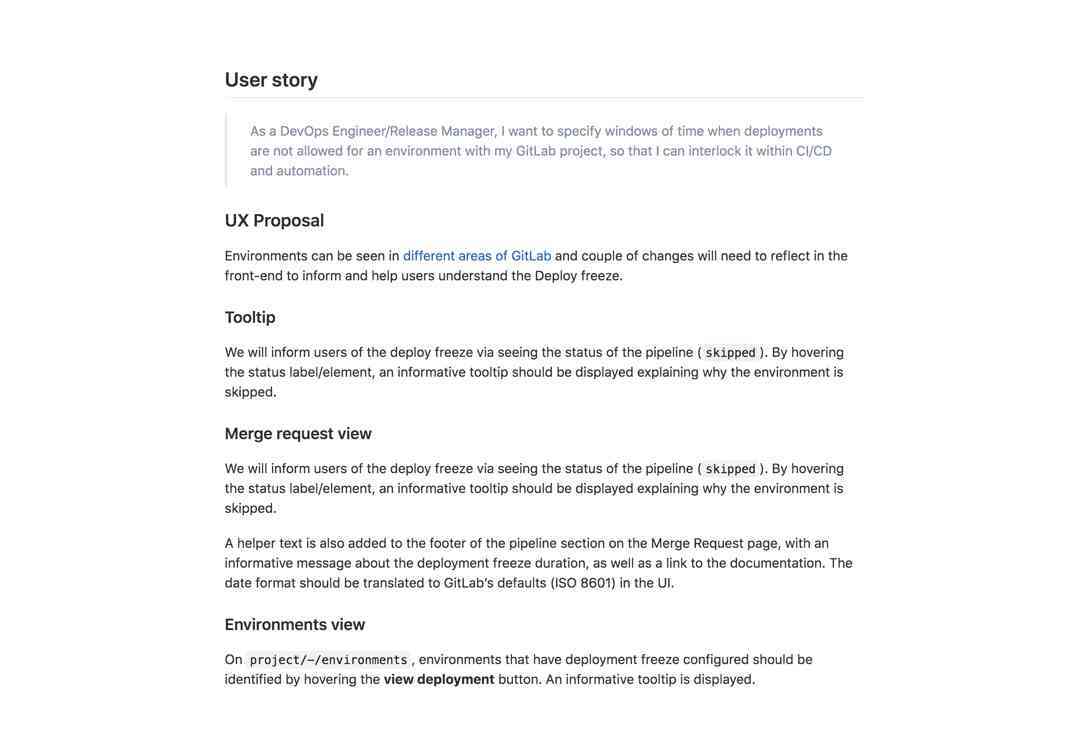

This is how one of the first versions of the MVC looked like:

High-level acceptance criteria including some interaction and requirements for frontend. No high-fidelity prototyping at this point.

A quick-and-dirty mockup produced by manipulating the source and styles of the Environments page on the browser.

Although engineering wanted to support the ability to configure everything related to a Deploy Freeze using the gitlab-ci.yml file at some point, while being able to retry a pipeline or even bypass a freeze period, we had significant data showing that it would be more valuable to users to instead have the ability to easily configure their policies using the UI. Our user insights told us that users configuring these kinds of pipelines are much less familiar with the terminal, and even editing yaml might be a challenge.

Iterate, iterate, iterate

Back to the drawing board (or, in my case, the GitLab issue). My focus shifted from simply notifying users to allowing them to enter data in the UI. We worked asynchronously on different proposals, until the point the scope could fit an MVC that satisfies the user goals we identified through research.

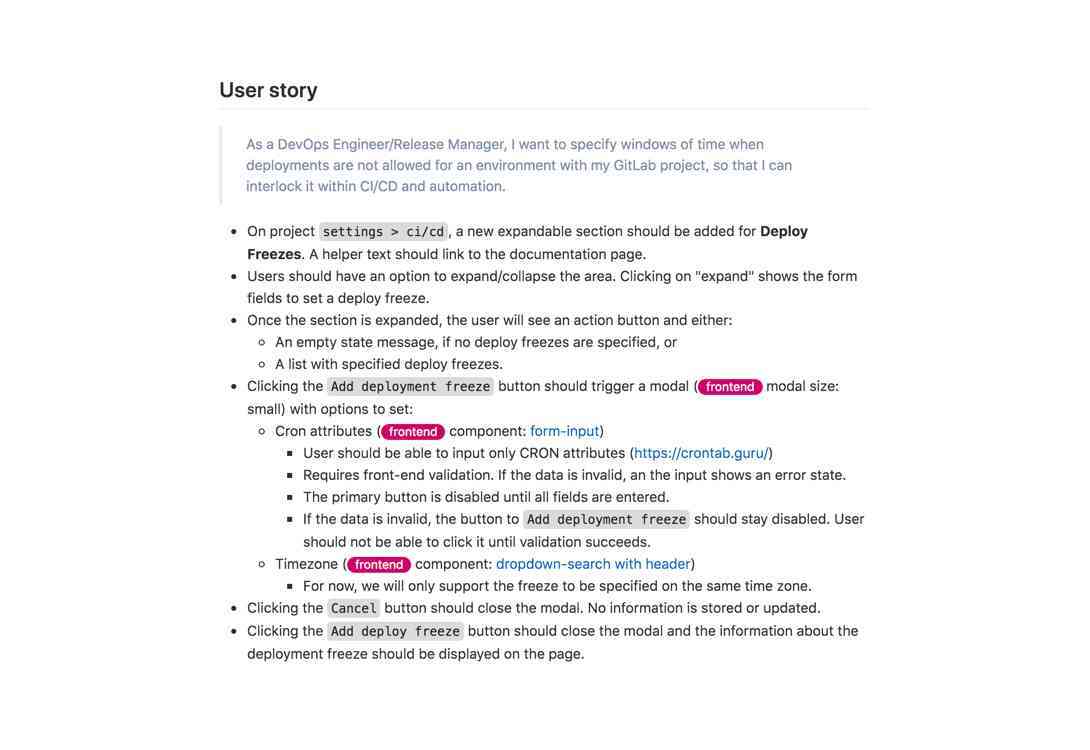

Using the same user story, the acceptance criteria shifted to:

While working on the new acceptance criteria, I started raising a couple of questions and thinking of edge cases. For example, "can we use a date picker UI component to select the deploy freeze period?", "will the end freeze field always be mandatory when setting a new period?", "can we support the user's default browser timezone when showing a dropdown on the UI?", and "how do we validate the cron syntax on the frontend?".

Once again, Engineers to the rescue! Nathan, our Super-Frontend Engineer, and I had a quick call where I walked him through my low-fidelity prototypes and we aligned our goals. Our decisions were documented as a comment on the MVC to ensure everyone involved could access the information.

Break the user story down into something even smaller

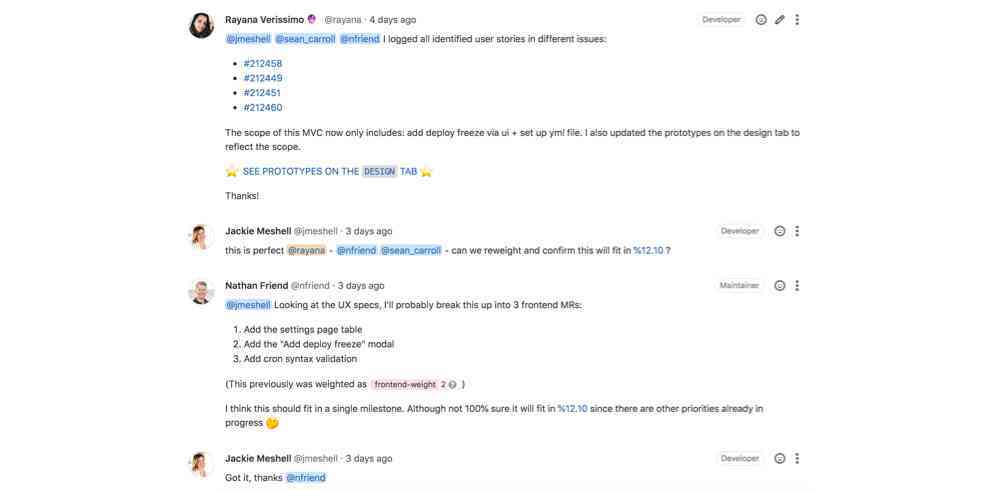

My conversation with Nathan also made it clear that editing and deleting a deployment freeze using the UI, as well as showing human-readable cron syntax descriptions, would increase the MVC scope. Because of that, I proactively broke the user story down into four new user stories that were logged as new feature proposals:

As a user, I want to see human-readable cron syntax descriptions for deploy freezes in GitLab's UI, so that I can easily understand the information about a freeze. gitlab#212458

As a DevOps Engineer/Release Manager, I want to edit Deploy Freezes I specify, so that I can keep my information up to date. gitlab#212449

As a DevOps Engineer/Release Manager, I want to delete deployment freezes I specified, so that I can keep my information up to date. gitlab#212451

As a user, I want to be informed when a Deploy Freeze is active for my project in GitLab, so that I can stay up to date with the status of production deployments. gitlab#212460

By reducing the scope of the MVC, the Product Manager and Engineers could start a new conversation about delivery efforts:

Async discussion and frontend estimation of the MVC. Read more on gitlab#24295

I then placed the descoped stories in the “backlog” for short-term assignment and long-term reference. By having our Product Manager serve as gatekeeper to the backlog, our team can focus on working on high-value features that have already been vetted and are supported by user insights.

Prototyping with a focus

With everyone on board, I can finally spend proper time prototyping the MVC solution! 🎉

I personally am a fan of spending more time writing down design specifications than pushing pixels. Because the GitLab train is always moving, prototyping is costly and prone to becoming obsolete in the blink of an eye. I also try to be mindful when I need to provide a prototype to my team. Will it help them understand my proposal? Can the prototype unlock hidden edge cases I didn't account for? Do I work with people that need visual cues to better understand the design goals?

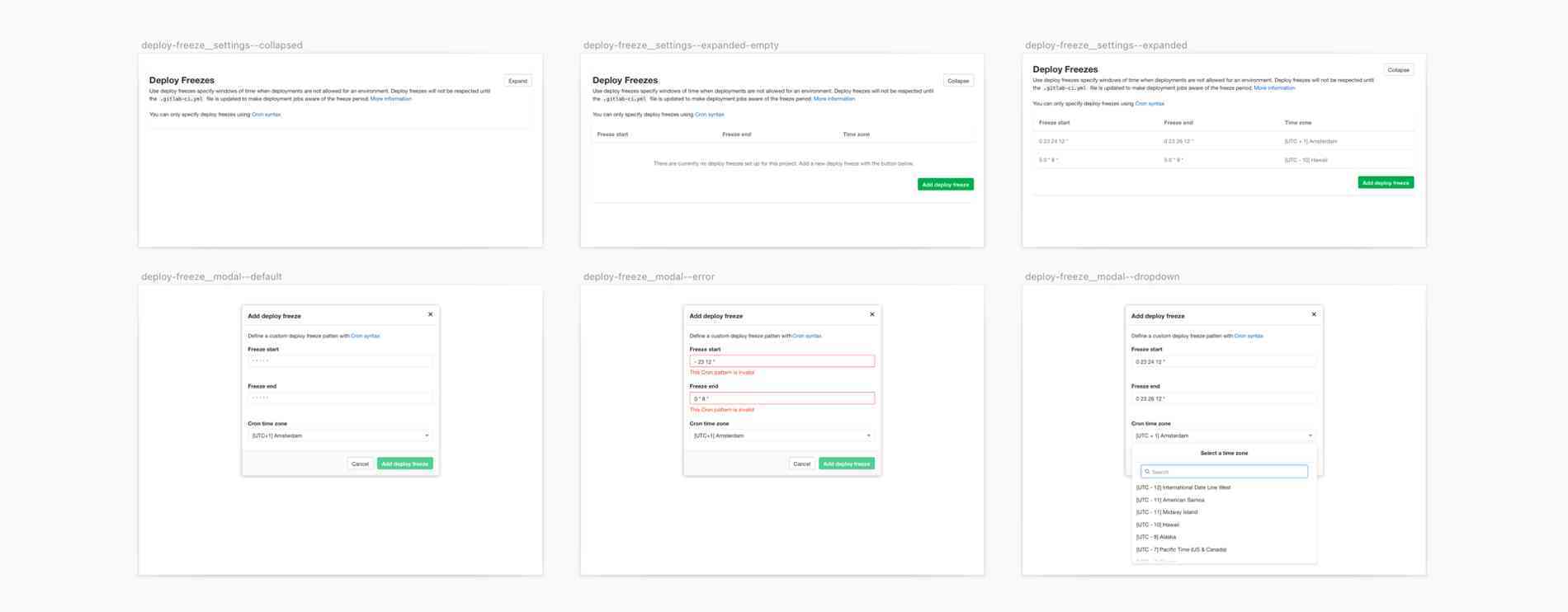

Final high-fidelity prototypes used by the engineering team to estimate the MVC. Adjustments of UI copy are aligned on the fly with Technical writers after this phase.

Previously, Pedro shared how one of the designer’s responsibilities is handing off the design to developers, so that it gets implemented as intended. I trust that my frontend team will follow the acceptance criteria, for example, by reusing the Pajamas components I specified. And if by any chance they need to make changes/improvements to the design proposal on the fly: so be it!

The prototypes I build facilitate the design/development conversation, and they are meant to be used as assets to help our engineers have a starting point to build features. Prototypes are not the end product! Because I am also added as a UX reviewer to frontend merge requests, I can spot inconsistencies under development and discuss the proposed changes on the fly with the team. Once we agree on a direction, and if the change is big enough to be noted on the scope of our MVC, I make sure the information is updated in the SSOT.

Five keys takeaways from our workflow

- You don't need to do Agile to be agile (lower case a). Work around implementing best practices that work for you and your team.

- Communicate with your team early and often. As a tool, user stories help facilitate the conversation between UX, Research, Engineering, and Product. Look at the user stories to estimate design and development effort.

- Identify user stories before jumping into designing a "solution." Make an effort to use research insights to guide your decisions. Deliver on real user needs. If user data is not available, try looking into different research methods.

- Play around with the acceptance criteria. For each user story, see if it can be broken down into smaller, more specific stories.

- Document, iterate, and validate your decisions.

Where do we go from here?

As with everything we do, this process is in constant change. User stories have been a great ally to promote a shared vision of the end user, while shifting the way we ship solutions. We went from having a list of functionalities with dubious origins that simply focused on solutions to having user-centered proposals that clearly let us communicate why we are building things and how we want to help our users achieve their goals.

I am beyond excited about the relationship the Release Management team built around design and research. We are confident with the solution proposed for Deploy Freezes, but further developments may require solution validation to test the usability of our prototypes and implemented features. Personally, I would still like to uncover more opportunities to contribute to gitlab-ui components and the Pajamas Design System through our user stories, so that we can come up with additional improvements to patterns that are used globally across GitLab.

If any of these topics interest you or if you have some feedback on our ideas, please get in touch and let us know what you think. We are planning great things for Release Management, in particular Release Orchestration with GitLab.

You can get to know more about the Release UX Team Strategy in our handbook! We would love to hear from you!

Cover image by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash