Published on: August 13, 2020

14 min read

The developer-security divide: frank talk from both sides

Data from our 2020 DevSecOps Survey shows dev and sec remain at odds over test, bug finding, fixes, and more. Can we be friends? Maybe.

We have to start by saying that at GitLab, there really is no developer-security divide. Dev and sec do get along – extraordinarily well, as a matter of fact. But there’s no denying that friction between developers and security pros does exist and we wanted to take this opportunity to acknowledge the elephant in the room.

In our 2020 Global DevSecOps Survey, 65% of security pros said their organizations had successfully shifted security left. Thanks to DevOps, developers, security experts, operations professionals, and testers all reported being increasingly part of cross-functional teams dedicated to getting safe code out the door more quickly.

But look a bit more closely into that rosy picture and the cracks start to appear. Security team members said developers didn’t find enough bugs early in the process and were slow to fix them when they were found. Not enough security testing happens and if the tests are run, they occur too late in the process. Very few devs said they run standard security tests like SAST or DAST. And there is even confusion over exactly who is responsible for security: 32% of sec pros told us they were solely responsible but more than 29% told us everyone was responsible.

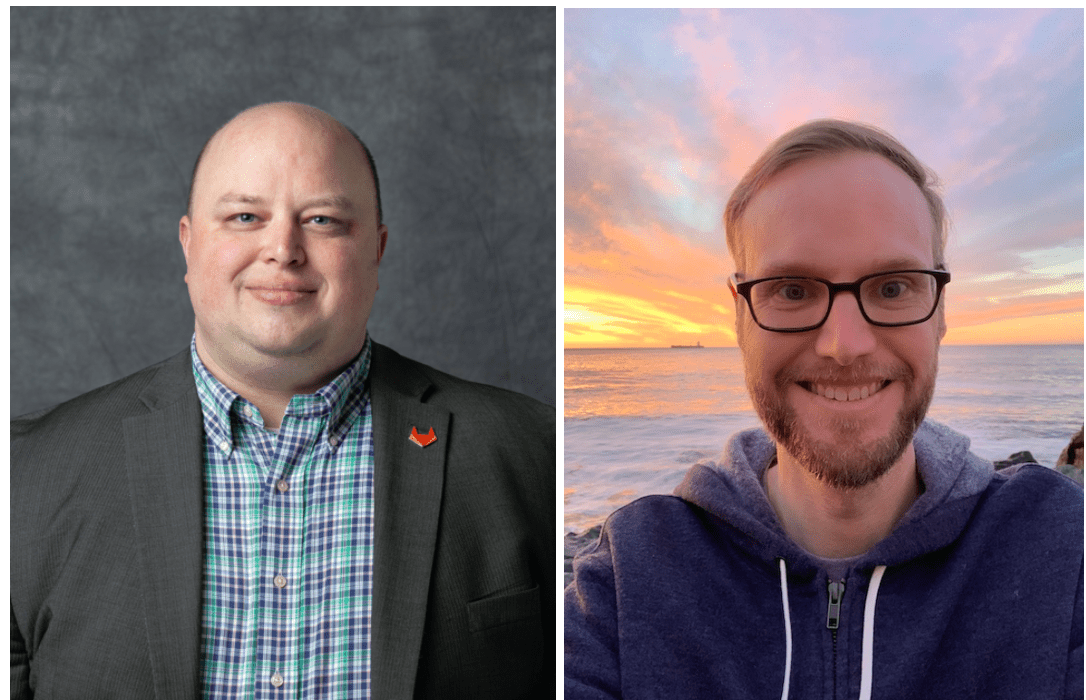

To see if we could shed some clarity on these critical-to-get-right DevOps topics Brendan O’Leary, senior developer evangelist, and Ethan Strike, security manager, Application Security, had a virtual sit down to hash out the differences between devs and sec.

{: .shadow.small.center}

Brendan O’Leary and Ethan Strike

{: .shadow.small.center}

Brendan O’Leary and Ethan Strike

Who is primarily responsible for security?

Ethan: Overall, for secure development to be successful there has to be a culture of security shared between all of the stakeholders, including development, product, and security. That means that both development and security need to feel trusted and supported throughout the organization, not just in their particular vertical. Here at GitLab, our E-group has done an excellent job of building that culture, which has allowed us to tackle problems collaboratively across teams.

Specific to the question, in order to be successful, I believe the team writing the code is ultimately responsible for security. They are the owners of the code they write, and know it best, so they are in the best position to ensure its security. But that does not mean that the security team is off the hook for product vulnerabilities. They have the important responsibility of ensuring the development team has tools and knowledge available to them to write secure code. They might even contribute to the code base themselves.

For secure development to be successful there has to be a culture of security shared between all of the stakeholders. – Ethan Strike

The security team also has the important role of assessing risk and communicating that risk effectively for the development teams to act upon. It is unrealistic for both sides to expect the other to shoulder the entire security work load, and there must be a balance between security requirements and functionality based upon business requirements.

Brendan: There are two ways to look at this. If we said who is directly responsible for security, then sure it’s easy to say that the folks with "security" in their title are the answer to that.

But the reality, especially in a modern organization centered around software delivery and excellence, is that everyone has to be responsible for security and have it at the forefront of their minds.

The thing customers want is better software faster, but one security incident can make that irrelevant. Security thus is a key component of quality software, and has to be a team effort. Just as there are different folks on a car assembly line that are primarily responsible for different parts of the car, the only way for a high-quality vehicle to roll off the end of the line is for everyone to work together, back each other up, and help to check each other's specialized work.

Devs aren’t running enough SAST/DAST/container or compliance scans. Why?

Brendan: The bar is far too high to even get started running SAST or DAST scans. Let’s take a look at them separately as they are worlds apart.

So running the code in production is hard enough, why would I spend time to try and run it before production? – Brendan O’Leary

For SAST (or container or compliance) scans: To run that as a developer in a "traditional" organization, I would need help from the ops team to have the right tooling installed. To determine what the "right" tooling is, I’d probably need a security review of existing tools as they are varied and their efficacy can depend on what languages and frameworks we are specifically using to write our application. And all of that work is before the first SAST check even runs - and after they are running it’s even worse. As a developer, I don’t have a great way to understand at the end of a release cycle what changes caused which security issues, so the "noise" of security tests (if we have them) is too loud to find the signal inside. It’s easier to just not deal with that whole cycle.

For DAST the bar is much higher than even SAST. While I have all the same issues that we mentioned about SAST in terms of coronation and signal-to-noise ratios, now add that complexity to the fact that I will need an entire running "prod-like" environment to even think about running DAST. That means recreating a proxy for the network and architecture decisions that are made by the ops team about the production environment. And if you get the wrong thing wrong, it makes all of the DAST test invalid. So running the code in production is hard enough, why would I spend time to try and run it before production?

Ethan: In my experience this is because out of the box the tools can create a lot of noise. Common causes of noise are false positives, or a high number of low-impact findings. When you’re trying to get a feature out the door, this can understandably be frustrating. A lot of the noise comes from the generic nature of the tools, as they are meant to be applicable to every code base. Each code base is of course different.

Here again though, some cooperation can go a long way. The efficacy of the tools comes with some tuning, and the goal is to get to that happy medium. For example, at GitLab, the results of the SAST tools are presented in an MR and developers are first in line for validating the findings, as they know the code the best. The application security team also looks at the results in the dashboard, and is looking to assess larger trends, identifying areas that are being overlooked/dismissed incorrectly, or simply providing additional context on the findings. That information can then be shared with the development teams. Each side has to trust that the other is working to find the right balance.

Why aren’t devs finding enough bugs?

Ethan: This is difficult to answer, as it is driven by the circumstances. It could be a matter of security education, a feeling of lack of ownership, or just culture overall. I think that most developers, if given ownership of the code they write, would be incentivized to find as many bugs as possible. In the end, that means less time fixing things in the backlog and more time building features. In order to do that though, they need to be given resources in the form of knowledge and time to test effectively, and the security team can help them with that.

Brendan: This is a direct result of the above. In fact, given how few developers are running SAST and DAST, it may honestly be generous to say they discover 25% of bugs. Without that infrastructure, there’s no way for me as a developer to find those issues.

And worse than that they can all be "out of sight, out of mind." If security has a walled garden around information about what security scans are important to our organization, or how to run those scans, then I’m just as happy as a developer to live in an "ignorance is bliss" world. That is of course until there’s a major security breach caused by poor coding practices.

How can bugs be found earlier in the process?

Brendan: Again, the bar is too high to run the security scans. As a developer, I don’t have an easy way to do that or understand security’s requirements for those tests. Without that ability, I’m at a loss to find any bugs.

And without any "security" in the pipeline, it leaves all detection of security issues to the end of a cycle when we want to actually put the code into production. And by that time, there have been dozens or hundreds of changes, so unwinding what changes caused which issues is next to impossible - much less understanding how to quickly fix them. So it’s back to the drawing board from an engineering perspective to fix issues we should have known about when we started walking down that path... of course this causes delays.

If security has a walled garden around information about what security scans are important to our organization, or how to run those scans, then I’m just as happy as a developer to live in an "ignorance is bliss" world. – Brendan

Ethan: That is because testing in general comes late in the development process. I don’t think this is always security specific. This stems historically from the waterfall software development process. With agile, quality testing has become more prominent with unit testing and CI, but security is still working its way into that workflow. For example, at GitLab, we have security focused unit tests and automated SAST and dependency scanners, but we still have manual security testing, and a bug bounty program in operation after major development is complete. I think that all security teams are always looking to find ways to identify a risk when the code is written. This can be in the form of threat modeling, embedded security engineers looking at code, and the development of security-focused libraries.

Is it true that devs apparently don’t want to fix bugs?

Ethan: I do not think that is true. I think that there can be difficulty scheduling fixes in with feature requirements. Also, if I remember correctly, in the survey, some developers said that they do not always know how to fix a bug. I think that the fixing of security bugs needs to be a cultural practice within the company. All teams involved in development, including product, developers and the security team have to be committed to fixing security bugs within established time frames. That also has to be balanced with features and non-security bugs. That is where an agreed upon SLA for fixing security vulnerabilities is helpful.

Brendan: I love to fix bugs - when they are easy to identify and debug and small enough to make the "blast radius" of a fix not too large. The best time to do that is when I’m in "flow" - right when I’m writing the code and have a mental model of all of the things and how they are interconnected. So that’s basically the same day or same week as when I wrote it.

With agile, quality testing has become more prominent with unit testing and CI, but security is still working its way into that workflow. – Ethan

After that, if I find out about a bug weeks later or that is only reproducible in production, then it is extremely frustrating if not impossible to fix. Without an environment that looks like prod, or a clear understanding of why security sees something as a bug that I see as a nuance, it makes it much harder to fix.

If I was given the feedback I get at the end of a release cycle on the day I write the code, bugs would get fixed immediately.

Are security pros seen as too "top down" and "out of touch" with programming?

Brendan: Oftentimes security and developers seem at odds. In many traditional organizations, this is both cultural AND related to misaligned incentives. If we only incentivize developers by the speed at which they are able to release new features while also incentivizing security professionals by number of incidents then the two are constantly at odds.

This is the same dichotomy of relationship that existed (and still does in some places) between developers and operators. If the only goal is fast feature shipping, you move fast and break things. If the only goal is a stable operating environment, then you’ll make sure no one is able to easily change or add anything.

That’s why the term "DevOps" was invented - to try and align incentives. Many organizations still struggle with that, but the DORA research has shown us that the two can actually complement each other if we focus on the metrics that really matter (frequency of deploys, time to fix an incident if one starts, etc.). What are those same metrics that will bring security and development together? They are probably very similar, but until organizations accept that and focus on cultural change to make sure that the teams incentives are truly aligned, it will continue to be a struggle.

Ethan: This has not been my experience at GitLab. It really depends on how the security team was built. At GitLab, we like to believe that we’ve built a balanced team that covers the range of security skills, from lots of development experience and deep knowledge of secure coding techniques, to more dynamic security testing-oriented engineers who are working on building up their development skill set. Each of them are important to building a security program that enables and supports developers in building secure products.

Finally, will dev and sec ever get on the same page?

Ethan: We need a realignment of expectations and support at all levels for developing a secure product. On the security side, the team has to realize that there will always be vulnerabilities that get to production. There is no way to catch them all. This is not only because of the fast nature of software development, but also because new attack vectors are discovered, and some things, like newly identified vulnerabilities in dependencies, are only identified after deployment. With that in mind, they should work towards providing developers the tools and data needed to identify them as early as possible, especially those vulnerabilities that are seen repeatedly. Also, there should be a well-known policy for handling vulnerabilities that are identified. That way, everyone knows what to do, and expectations are clearly defined.

If we only incentivize developers by the speed at which they are able to release new features while also incentivizing security professionals by number of incidents then the two are constantly at odds. – Brendan

From the engineering side, it’s important to accept security as part of your development flow. It’s not glamorous, but the reason security is important is that it builds trust with customers and other stakeholders in your product. It also protects the company. Help the security team. This can be done by identifying areas of concern, asking questions, and helping security team members understand the code being written. For both teams, it’s important to have constructive communication and collaboration. There should be regular communication about what each team considers important and how that can be attained. Above all, there must be trust that the other team is doing what is best for the product.

Brendan: Much like the last 10 years has seen businesses make themselves successful (or fail) based on their ability to deploy changes quickly and create a stable service, the next 10 years will see a similar transformation around security. The import of things like security, privacy, and data protection will require it of businesses, and those who are not able to adapt their culture will fade away. Those who have a radically different view of the world will thrive.

In the end, this is how dev and sec will "have" to get along.

Our 2022 Global DevSecOps Survey is out now! Learn the latest in DevOps insights from over 5,000 DevOps professionals.

Read more about development and security:

- How secure is GitLab?

- How we think about security and open source software

- GitLab's guide to safe deployment practices

Cover image by Marcus Winkler on Unsplash

We want to hear from you

Enjoyed reading this blog post or have questions or feedback? Share your thoughts by creating a new topic in the GitLab community forum.

Share your feedback